Climate and Clean Energy Grantmaking

Table of Contents

(Creative Commons/Chris Bentley)

During The John Merck Fund’s lifetime, grantmaking in the field of climate protection and clean energy was not for the faint of heart—especially in the case of small foundations like ours. Hurdles included the sheer pervasiveness of oil, gas, and coal in the world economy, the fossil fuel industry’s deep-pocketed defense of the use of fossil fuels, and the public’s wariness—exploited by industry-aligned politicians—of solutions that might boost prices at the gasoline pump.

Yet climate and energy nevertheless became a core JMF funding area, propelled by our trustees’ deep concern about the dangers of continued fossil fuel dependence and by their confidence in alternative approaches charted by an array of superb grantees. Our grantmaking in the field ran continuously from 1987 to the end of our spendout, a span of 35 years, and it ultimately totaled $57.6 million—the Fund’s second-biggest spending area overall behind health and the environment.

The program’s path was anything but linear, reflecting the evolving—and, at times, devolving—nature of the climate and energy debate, as well as shifts in our own perceptions of how and where our limited resources could make the greatest difference.

Some course corrections paid off handsomely, particularly our decisions to focus on a single region, New England, and on state-level policies and programs rather than on national initiatives. There were some stumbles, several involving efforts to put a price on carbon. And there were missed opportunities, such as our failure to embrace environmental justice advocacy earlier and more extensively than we did.

As our spendout concluded, however, we could look back on a record of remarkable impact, with JMF-funded grantees playing a leadership role in:

- Hastening the closure of New England’s coal-fired power plants;

- Blunting the fossil fuel industry’s efforts to promote long-term regional dependence on natural gas, coal’s initial replacement;

- Birthing a regional clean energy market and making New England the country’s leader in energy efficiency;

- Accelerating the region’s transition to renewable electricity through the development of distributed and large-scale solar, offshore wind, and renewable energy storage;

- Encouraging state public utility commissions and ISO New England (the federally designated entity that runs the region’s electric-power grid) to integrate clean energy more fully into state and regional electric systems;

- Establishing a 10-state initiative in the Northeast that caps power plant emissions and raises money for energy-efficiency work and other projects through the auction of emissions credits;

- Spurring plans for New England clean-transportation initiatives with a focus on electrification of cars, trucks, and buses;

- Enacting mandates for carbon emission reductions in all but one New England state; and

- Cultivating a vibrant ecosystem of climate and energy advocacy throughout the region.

Though these advances occurred against a backdrop of inadequate climate and energy action regionally and nationally, they inspired important grassroots, policy, and market progress. That progress occurred not only in New England, but also had significant ripple effects beyond, according to Douglas Foy, former president of Conservation Law Foundation (CLF), one of New England’s leading environmental advocacy groups.

“If you can build successful policy models in New England, you have models that can be taken to a national scale, given the different state politics and issues you encounter in the region,” Foy said in an interview in 2022. “We never would have made the climate and energy progress we did, both regionally and nationally, but for the work that The John Merck Fund nurtured at Conservation Law Foundation and other organizations.”

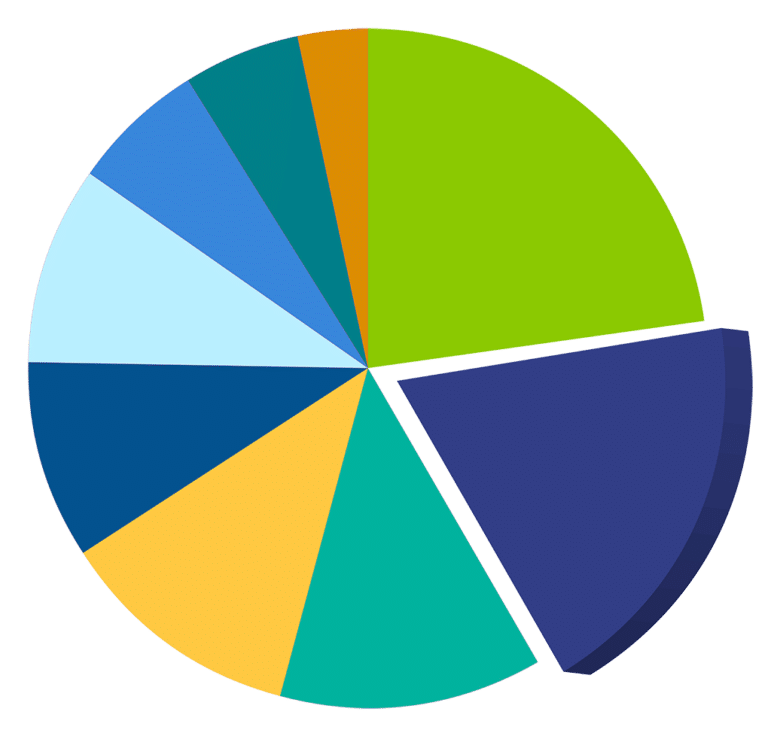

JMF Grants 1986-2021: Climate and Clean Energy

Total $ Amount

$57,625,018

Years of Program

1986-2021

# of Grants

928

Early days

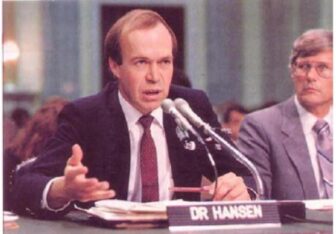

Our Fund entered the climate and energy field in 1987, as scientists were issuing some of their earliest public warnings about the global climate impact of human-caused carbon emissions. Among the most widely reported of these came on June 23, 1988, when NASA scientist James Hansen told a U.S. Senate hearing that “the greenhouse effect has been detected and is changing our climate now.” His testimony received front-page coverage in The New York Times.

(NASA Image Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

Our first grants supported energy-efficiency advocacy, which over the decades would become a leitmotif of The John Merck Fund’s climate and energy grantmaking. Specifically, this early funding helped launch a Conservation Law Foundation electric-power efficiency initiative that began in Massachusetts and then extended to other states in the region.

Driving the initiative was a deceptively simple concept that was developed in New England in the mid-1980s and eventually influenced state policymakers nationwide. It held that energy conservation represented an enormous reservoir of new electricity that, if exploited and expanded with regulatory incentives and technological improvements, could dramatically reduce the need for new power plants and eventually redirect energy demand downward.

The program’s early years also included funding of energy-efficiency and solar-power projects in Eastern Europe and the Global South. But by 1995, we had concentrated the bulk of the program’s grantmaking on a national-level U.S. campaign to raise public awareness about the dangers of fossil fuel dependence.

Specifically, we helped fund Clear the Air, a coalition of advocacy groups pushing to strengthen the U.S. Clean Air Act. Coordinated by the National Environmental Trust, Clear the Air’s partner groups included Clean Air Task Force and U.S. PIRG. The Pew Charitable Trusts and other large foundations provided the lion’s share of the funding support.

We remained a co-funder of Clear the Air until 2002, ending our involvement for two main reasons. The first was that our contributions were making less of a difference in relative terms, given the increasing commitments of larger foundations to national climate advocacy. And secondly, by then we had found what we considered a higher-impact use of our limited climate and energy dollars: seeding a campaign in New England to curb pollution from the region’s coal-fired power plants.

Coal campaign

Launched in 1997, the New England Power Plant Campaign sought to “clean up or close down” all 16 of New England’s coal-fired electric-power stations—six in Massachusetts, five in Connecticut, three in New Hampshire, and two in Maine. Undergirding the initiative was pioneering analysis of emissions-tracking and health-effects data developed by Clean Air Task Force and its visionary leader, Armond Cohen, in partnership with the Harvard School of Public Health.

Clean Air Task Force

This analysis created crucial new traction. That’s because in the 1980s, coal-power opponents had focused mainly on the long-range transport of airborne pollutants from upwind Midwestern power plants, highlighting the acid-rain toll these emissions were taking on lakes and streams in Eastern states. Although reports of this damage captured public attention, Clean Air Task Force’s collaboration with the Harvard School of Public Health documented another, more immediate cause for concern: the health problems that coal-fired power stations were causing in communities within 150 miles of their stacks. Illuminating this connection allowed the fight against coal-plant pollution to be waged on local public health grounds, not only in the context of climate protection and ecosystem preservation.

A regionwide coalition of grassroots advocacy groups partnered in the initiative, informally called the “Sooty 16” campaign. Clean Water Fund co-led the charge in Massachusetts in partnership with Massachusetts Public Interest Research Group, which served as the New England–wide coordinator. Toxics Action Center—later renamed Community Action Works—headed the campaign in Connecticut and coordinated with Clean Water Fund to direct activities in New Hampshire. Meanwhile, the Natural Resources Council of Maine headed the campaign in that state. Advocacy members developed communications strategies collectively, then tailored them individually according to what would be most effective in each state.

A range of funding partners joined JMF to underwrite the campaign—among them the Energy Foundation, the Cox Trust, the Growald Foundation, the Merck Family Fund (a JMF sister foundation), the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the Rockefeller Family Fund, and the Tremaine Foundation.

As consensus grew that New England’s coal-fired power stations could not be “cleaned up,” the campaign concentrated on shutting them down. Natural gas–drilling technology and market forces provided momentum as hydraulic fracturing made gas both plentiful and cheap enough to begin displacing coal as a feedstock for power plants.

But the path from coal to truly clean power sources was neither clear nor guaranteed, particularly in the campaign’s early years. A prime reason was that coal-fired plants were deeply embedded in the region, generating not only a sizable share of New England’s electricity, but also local jobs and tax revenues.

Further complicating matters, renewable energy was in a relatively early stage of development and thus cost more to produce than power from fossil fuels. It was uncertain where carbon-free replacements for coal—as opposed to natural gas, another fossil fuel—would come from, and what the economic impact of a transition to them would be.

All of this put a premium on grassroots engagement. Local campaigns required increasingly specialized information and organizational guidance as they reached out to different constituencies regarding not only health questions, but also economic issues such as the tax and employment impacts of plant closures. For instance, Clean Water Fund, under the leadership of New England Director Cindy Luppi, responded with customized “deep organizing” in towns adjacent to the Brayton Point plant, the region’s largest coal power station, located in Somerset, Massachusetts, near the Rhode Island border.

Clean Water Fund

New grassroots partners joined over time. The Connecticut Coalition for Environmental Justice and Toxics Action Center worked with Black and Brown communities living near the coal plant in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Another group, Neighbor to Neighbor, in Holyoke, Massachusetts, worked with leaders in the city’s Puerto Rican community to help build an advocacy campaign targeting the coal-fired Mount Tom power plant, tapping deep concern about the plant’s health impacts. In doing so, the campaign broke new ground by expanding its goal from closure of the power station to replacement of it with a renewable energy facility.

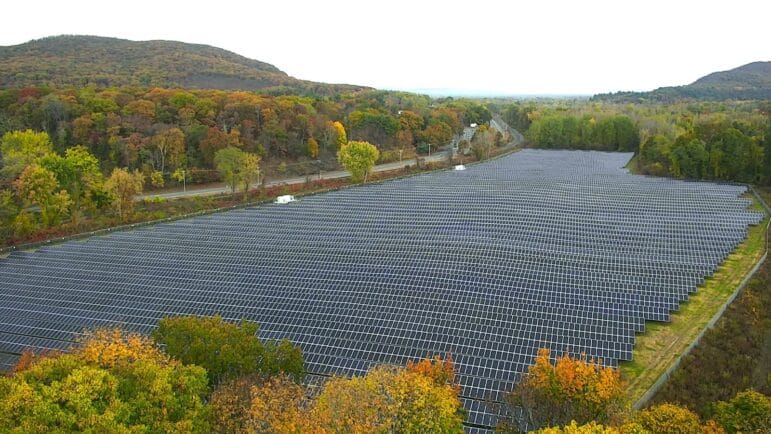

Working with Holyoke community groups, elected officials, and others, Neighbor to Neighbor and its partners engaged directly with the plant’s owner—France-based GDF Suez, later renamed Engie. Their “Coal to Sol” campaign successfully pressed the French multinational to dismantle the coal station and replace it with a large solar plant, in the process providing severance packages for workers who would lose their jobs. The array, built in 2016 and featuring some 17,000 solar panels on 22 acres, has an installed capacity of 5.76 megawatts—enough to power 1,000 homes—and a battery system capable of storing 3 to 5 megawatts of power.

For Lena Entin, Neighbor to Neighbor’s lead organizer in the Mount Tom campaign, the initiative and leadership shown by community members made all the difference. Said Entin in 2022: “As organizers, we know that when communities that are most impacted take the lead and develop their own vision of what should happen, that is when you get the groundbreaking victories. The neighbors did not want to see that plant go from coal to natural gas. From the beginning, they wanted a transition to renewable power.”

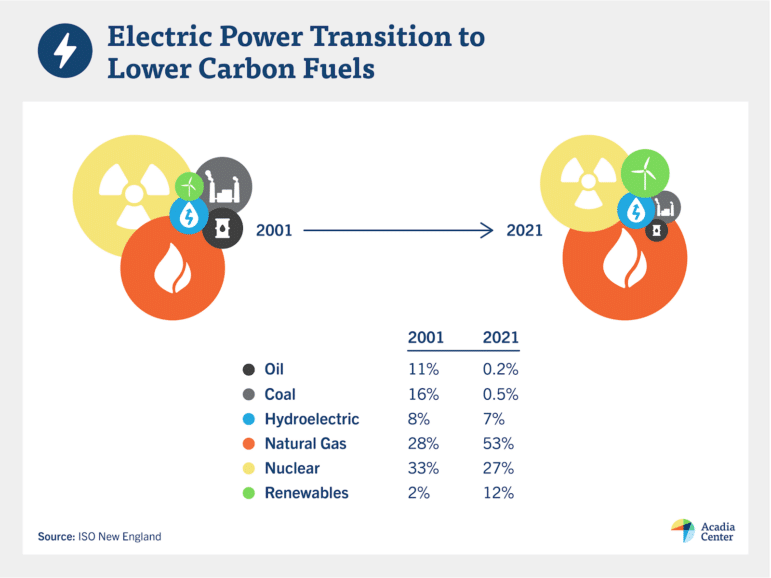

By 2021, The John Merck Fund’s final year of grantmaking, all of New England’s coal-fired power stations had closed with the exception of two relatively small “peaker” plants in New Hampshire dedicated to providing power in periods of high demand. Regionwide, coal- and oil-fired plants represented 0.5% and 0.2%, respectively, of the region’s electricity generation, compared with 16% and 11% in 2001.

Early success in New England organizing prompted our board to support similar coal plant campaigning in the Midwest from 2002 to 2010, along with a related effort in that region to spotlight the health impacts of diesel transportation fuel. For Ruth Hennig, longtime JMF executive director, the combination of health-impact data and grassroots organizing employed in New England created a compelling template for bringing the dangers of fossil fuel combustion home to communities.

“The science enabled the coal plant activists to use a human-health frame,” said Hennig, who after stepping down as executive director served on our board through the end of the spendout. “New Englanders started to connect the nearby coal plant with health problems their families were experiencing. Now they were saying, ‘I’m worried about that coal plant down the road because it could be the reason my child has asthma.’”

(Courtesy of Tighe & Bond)

Greening the market

In addition to supporting advocacy that targeted pollution sources directly, we also backed efforts to use market forces to drive energy-efficiency and clean-power progress, including some initiatives that sought to put a price on carbon.

We contributed to six separate state carbon-tax campaigns from 2007 to 2019—in Massachusetts, Vermont, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Washington, and Oregon. Each of these campaigns foundered amid industry opposition and consumer fears of increased fuel and energy prices. However, an earlier initiative featuring a different approach to carbon pricing—development in the Northeast of the country’s first multi-state carbon cap-and-trade program—took root.

In that project, we joined a coalition of funders led by the Energy Foundation in 2005 to help birth the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). Launched in 2009, the 10-state initiative established caps on power plant emissions coupled with the auction of emissions credits to raise millions of dollars annually, mostly for energy-efficiency programs.

Other grants aimed to grow and diversify consumer demand for renewable power systems—such as rooftop solar and home energy-efficiency improvements. In one such effort, grantees Interfaith Power and Light, Regeneration Project, and Connecticut Coalition for Environmental Justice encouraged members of faith-based groups to use renewables as a means of improving stewardship of the world.

In another effort, we collaborated with four foundations to lay the groundwork for a Connecticut-based nonprofit dedicated to boosting consumer demand for clean, renewable energy and energy efficiency in that state and across New England. The organization, SmartPower, collaborated with the Connecticut Clean Energy Fund (which later became the Connecticut Green Bank) and, under the leadership of founding President Brian F. Keane, went on to help build the consumer market for renewables across New England and in other regions.

Working with community groups and researchers from Yale University’s School of the Environment and the Stern School of Business at New York University, SmartPower designed and launched Solarize, a model for on-the-ground and online residential solar outreach. Solarize campaigns in a three-year period generated more than $100 million of installed residential solar in Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire. The grassroots-driven model also attracted the interest of the U.S. State Department and the government of India, where it was used successfully in New Delhi.

We also supported efforts to press corporations and institutional investors to reckon with climate change–related risk and other environmental-sustainability challenges. An early and influential source of such advocacy was Ceres, a Boston-based nonprofit. Beginning in 2000, we provided grants to support Ceres’s work in New England as part of its efforts to push corporate sustainability nationwide. Ceres also brought business and investment leaders into policy discussions that led to initiatives in New England ranging from the RGGI cap-and-trade initiative to climate tax credits.

“In the early days we were saying to corporate boards, fiduciaries, and governance bodies that there’s no point thinking in the long term if you don’t think about issues like climate, toxics, and water,” Mindy Lubber, Ceres’s longtime CEO and president, said in 2022. “It was a completely odd notion, and it took years, but now almost every Fortune 500 company has a sustainability committee and metrics to hold itself accountable. And every stock exchange and credit agency is talking with us about building a sustainability screen. We made climate, toxics, and water capital-markets issues.”

Changing utilities’ ways

Efforts to build markets for renewable power and energy efficiency benefited enormously from the work of grantees pushing state-level utility reform, among them key regional advocates Acadia Center, Conservation Law Foundation, and Northeast Clean Energy Council Institute.

This work included successful campaigns in New England for state policies requiring utilities to establish “system benefit funds” that underwrite energy-efficiency programs. These programs spurred the installation of everything from insulation, smart thermostats, and heat pumps in homes to high-efficiency chillers and motors in industrial plants. The resulting demand for such improvements, in turn, helped stimulate the formation of businesses to meet it, producing impressive results for the region. Beginning in 2006, New England regularly ranked as the nation’s leader in regional energy efficiency, according to a respected scorecard published by the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy (ACEEE).

The regional advocacy organizations and in-state grantee groups ranging from Save the Sound in Connecticut to Natural Resources Council of Maine also prodded New England states to bring two crucial tools to bear in developing the regional clean power market:

- Renewable portfolio standards, which require utilities to buy a certain percentage of their electricity from renewable sources; and

- Solar net metering, which requires utilities to purchase energy generated by their customers’ own solar systems.

Our grantee partners pushed other policies aimed at reshaping the electric-utility sector:

- The Green Energy Consumers Alliance created innovative programs to help municipalities buy clean energy in bulk on behalf of their residents and businesses, include green-power offers on utility bills, and establish electric vehicle purchasing groups;

- The Northeast Clean Energy Council Institute assembled a network of clean energy companies to promote policies favorable to solar- and wind-power development; and

- The Regulatory Assistance Project worked with utility regulators and advocates to ensure clean energy producers gain access to the grid.

(Acadia Center)

The overarching accomplishment of these and other policy initiatives was to break the New England electric-utility sector’s pattern of responding reflexively to rising electricity demand with construction of more fossil fuel plants and related infrastructure.

By ensuring that energy efficiency and renewable power received due consideration in energy planning, advocates helped the region do more than restrain greenhouse-gas emissions. That’s because energy-efficiency programs, while funded through surcharges on utility bills, delivered important economic benefits to ratepayers.

“It’s an unsung story, but the funds from efficiency programs get invested in people’s homes and businesses, which means you’re actually improving the quality of people’s lives,” Acadia Center President Dan Sosland said in an interview in 2022.

No less important, efficiency gains also saved ratepayers from being saddled with the cost of capital spending on fossil-fuel-based utility infrastructure. Sosland cites a 2012 decision by ISO New England, the federally designated entity that runs the region’s electric-power grid, to incorporate energy savings from efficiency programs in the demand projections that underlie its plans for the regional power grid.

The policy change, made under pressure from advocacy groups, prompted ISO New England in 2013 to indefinitely defer over $400 million in transmission upgrades it had identified in two states in the region. Had the upgrades been carried out, Sosland notes, they would have been charged to ratepayers.

“That’s a pretty dramatic example of what happens when energy-efficiency programs reduce demand on the system,” Sosland said. “There’s a direct economic benefit to the people.”

Stretch-run strategizing

When we launched our spendout in 2012, it was no surprise that climate and energy was one of our four chosen focus areas. The challenge to end fossil fuel dependence had only become more urgent, and the consequences of the world’s failure to meet it more dire. Our experience with the New England coal campaign, utility reform, and advocacy for renewables had given us confidence that although we were a small foundation, we could make meaningful contributions to the field.

The question was how to get the most out of the $27,540,000 we would ultimately distribute in climate and energy grants over the coming decade. Our conclusion, in short, was that our greatest opportunity for impact lay in supporting state-level action. More particularly, we felt we should confine our focus to New England, where we had developed a network of trusted partners and where we felt advocates, policymakers, and the public were poised to make impressive strides.

The case for sticking to state-level grantmaking stemmed in part from a crippling lack of resolve at the federal level. After President Bill Clinton signed the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, his successor, George W. Bush, announced in 2001 that the United States would not implement it, questioning the science behind the agreement and warning of adverse economic impacts. And as we approached our spendout, a cap-and-trade bill supported by the administration of President Barack Obama died in the U.S. Senate in 2010 amid national economic concerns, heavy opposition by the fossil fuel industry, and—not least—Republican obstruction.

Against that backdrop, focusing on further progress at the state and regional levels made more sense than ever. We believed that states, as they so often have in our country’s past, could serve as proving grounds for new approaches. If those approaches were implemented successfully, states could effectively preserve climate and energy progress in times of federal backsliding.

And there was more federal backsliding—most damagingly after the 2016 election of President Donald Trump, who would withdraw the United States from the Paris Climate Agreement and carry out an unprecedented gutting of federal environmental protections. The rollbacks included the reversal of clean air and clean energy standards in a futile attempt to restore coal as a leading energy source.

Taking our limited resources into account, we settled on a multi-pronged funding approach intended to help broaden and deepen work toward a clean energy future in New England.

“Our calculation was that progress at the state level has more staying power when the federal pendulum swings,” Karen Harris, our longtime climate and energy consultant, said in 2021. “State policies help build renewable energy markets that continue to grow when there is little federal support, and they provide important models for action when opportunities arise.”

The ‘natural gas trap’

A top priority on that score was to ensure that as its coal-fired power plants closed, New England would turn as much as possible to renewable power rather than simply switch from coal to another fossil fuel—namely, natural gas.

The risk of the latter scenario occurring was real. As the use of coal to fuel power plants declined, natural gas filled the void. By 2015, New England counted on natural gas for over 45% of its electricity and heating. And gas developers were attempting to build major gas infrastructure that would effectively increase the region’s reliance on the fuel for both electricity generation and heating well into the future.

Natural gas had been touted for years as a “bridge fuel” between coal and renewable energy, but experts warned that gas carried its own considerable risks to public health and the climate. Further, with major gas-infrastructure investment being pushed by utilities, the fossil fuel industry threatened to lock in natural gas use for 50 years, dimming the prospects for a brisk transition to renewable power. The industry’s plans prompted renewable power supporters to warn of a “natural gas trap.”

A pair of pipeline projects—Northeast Energy Direct (NED) and Access Northeast (ANE)—became a major flashpoint for debate. If these two pipelines had been built, they would have added significantly to the flow of natural gas to New England states from four different shale formations around the country, bringing the number of major gas-transmission lines serving the region to seven.

(Craig Miller Productions/U.S. Department of Energy)

Three of our grantees, working within a larger regional campaign, organized pipeline opposition in important but different ways:

- Pipe Line Awareness Network for the Northeast (PLAN NE), an advocacy alliance operating on a shoestring budget, helped community groups along both routes oppose permitting and provide standing for legal challenges;

- Toxics Action Center, later renamed Community Action Works, worked with opponents living in low-income “fenceline” communities adjacent to pipeline and gas-plant project sites; and

- Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) assisted communities fighting eminent-domain proceedings for the projects and pressed state authorities in New England to justify the need for the pipelines. With all six New England states supporting major gas pipeline expansions into the region, CLF found itself challenging these proposals before the state utility commissions of every state in the region. CLF eventually sued the state of Massachusetts, obtaining an order from the Supreme Judicial Court prohibiting the commonwealth and its utilities from investing in the pipelines.

The NED and ANE projects were suspended in 2016 and 2017, respectively, due in no small part to the anti-pipeline campaigns, which are credited with preserving the region’s ability to embrace renewable power.

“The transition [to renewable energy] is daunting in many respects, but it would be much harder today if the NED or ANE pipelines had been approved and we had an associated new system of gas power plants and pipelines proliferating in the region,” said Greg Cunningham, a Conservation Law Foundation vice president and director of CLF’s clean energy and climate change program. “The energy-funding pie is only so big, so if more resources are steered toward gas, that affects the region’s ability to invest in wind and solar energy, and, for better or worse, to bring in hydropower.”

Offshore wind

Our spendout strategy also emphasized development of new renewable power capacity—not only by promoting solar energy advocacy, but also by supporting a regional push for offshore wind power. Impressed by the success of wind farms in Europe, we began providing support in 2011 for the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) and other organizations working to make the Northeast a U.S. focal point for the industry.

Advocates aimed to rebuild momentum amid the contention surrounding Cape Wind, New England’s first proposed offshore wind project. Planned for near-shore waters in Nantucket Sound and formally proposed in 2001, the project drew fierce criticism from influential Cape Cod homeowners.

(Creative Commons/Peter Bowden)

Cape Wind ultimately was canceled after litigation launched by opponents effectively forced it to miss its utility-contract deadlines, but wind advocates believed projects located farther offshore would fare better.

A 2013 auction of sites off Massachusetts and Rhode Island—the first-ever sale of wind-energy rights in U.S. federal waters—offered just such an opportunity. To build interest in this and future auctions, regional grantees CLF and the Northeast Clean Energy Council (NECEC) pressed Northeastern states to set targets for offshore wind capacity. It was hoped these targets would signal to project investors and developers that the region’s states were serious about building offshore wind into their energy plans.

The active and diverse coalition of pro-wind advocates, led by the National Wildlife Federation, worked on a variety of other fronts as well. These advocates sought to ensure offshore turbines would meet requirements aimed at safeguarding migrating whales, birds, and fish, and they educated policymakers and the public about the economic benefits wind power could bring to the region. They also advocated for state-level worker training and supply-chain programs that would encourage wind developers to use local labor and logistics, offsetting job losses caused by the closures of fossil fuel plants.

By 2021, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut had made state policy commitments effectively ensuring they all would obtain 8,300 megawatts of their electric power from offshore wind farms by 2030. Counting the commitments of New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina, pledges by East Coast states as of 2021 called for 39,000 megawatts in offshore wind-generating capacity by 2040.

Just one offshore U.S. wind farm had been built as of 2021, the last year of our spendout—a five-turbine, 30-megawatt facility completed in 2016, 3.8 miles off Block Island, Rhode Island.

(National Wildlife Federation)

Counting the two turbines installed off Virginia, the number of offshore turbines in the entire country totaled just seven fully two decades after the first wind farm—the ill-fated Cape Wind project—had been proposed.

But this state of affairs was about to change. Work had begun in 2021 on a large commercial project off Massachusetts that called for 62 turbines and 800 megawatts of installed capacity, with power production scheduled to start in 2023. Sited 15 miles off the island of Martha’s Vineyard, the Vineyard Wind project was expected to generate sufficient power to meet the energy needs of 400,000 homes and businesses while reducing carbon emissions by 1.6 million tons annually.

By December 2021, Massachusetts had approved further offshore development by both Vineyard Wind and another venture, Mayflower Wind. The state now had a total of 3,200 megawatts of future offshore wind-power capacity under contract, a generating capacity 60% greater than that of the Hoover Dam.

Evidence of emerging economic knock-on effects from wind power was becoming evident by 2021 as well. Interestingly, it included planned projects at two former coal plant sites—an undersea-cable factory at Brayton Point, in Somerset, Massachusetts, and a harborside storage and staging facility in Salem, Massachusetts—to support the installation and maintenance of offshore turbines.

(Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)

A decade of progress had fueled optimism that New England was at last poised to tap its enormous offshore-wind energy potential, and that other U.S. coastal regions would follow suit.

“The potential of offshore wind, particularly off New England, is almost immeasurable—by 2040, we could absolutely see offshore wind powering more than 50% of the region,” Amber Hewett, National Wildlife Federation’s offshore wind program director, said in 2022. “The political will we were lacking has really grown. We knew we had to be relentless and take the risk of going first, establishing a consistent presence in all the relevant statehouses and with the federal government. It is rewarding to look back and see that this work has played a part in lining up the laws, the leases, and the procurement contracts that have made it happen.”

Clean transportation

Transportation projects also figured prominently in the Fund’s climate and energy spendout grantmaking. By the start of the spendout, the electricity sector’s greenhouse gas output was in decline, thanks to coal plant closures, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), efficiency investments, and an increase in renewable energy on the grid. As a result, vehicles rather than power plants were now the region’s largest single source of carbon emissions. Meanwhile, other pollutants associated with tailpipe exhaust posed a public health threat—especially in the low-income communities too often adjacent to high-volume car and truck routes.

Promoting clean transportation, though, required a multipronged strategy given the broad array of stakeholders, which included consumers, auto manufacturers, oil refineries, utilities, and more. It also meant addressing a profusion of pollution sources—namely, New England’s millions of fossil fuel–powered cars and trucks.

(Vermont Energy Investment Corporation)

Initially, we focused on electrification of light vehicles. Our grantee partners successfully pressed New England states to create state tax rebates on electric-vehicle purchases, expand the region’s vehicle-charging network, and enact rules to cut vehicle-charging costs. As these efforts unfolded, we simultaneously expanded our grantmaking to promote electrification of buses and trucks.

(NESCAUM)

Grantee partners included Acadia Center, Union of Concerned Scientists, Ceres, Georgetown Climate Center, Plug In America, and Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management (NESCAUM). The in-state leads were Save the Sound, Vermont Energy Investment Corporation’s Drive Electric Vermont, and Green Energy Consumers Alliance (in Rhode Island and Massachusetts).

Individually and in combination, these organizations raised public awareness about the need and potential for electric vehicles. Plug In America, Sierra Club, and Drive Electric Vermont organized thousands of “Ride and Drive” events throughout the region. Green Energy Consumers Alliance created an electric-vehicle buyers group that became a model for a similar program in New York state. And NESCAUM—a nonprofit association of air-quality agencies in the New England states, New York, and New Jersey—worked with automakers and state agencies to conduct a regionwide “Drive Electric” marketing campaign.

(Vermont Energy Investment Corporation)

As clean-transportation efforts progressed, we funded a growing number of regional initiatives. Under one that NESCAUM helped broker, four New England states plus New Jersey and New York committed to ensure that by 2025, their fleets would include 3.3 million electric vehicles. Recognizing that pollutants from trucks and buses often pose health threats to low-income communities, NESCAUM also successfully pressed 15 states, including all the New England states except New Hampshire, to pledge that all of their medium- and heavy-duty vehicles would be electric by 2050.

Alongside our successes, some of our regional initiatives fell short. A potentially game-changing initiative that failed was the Transportation and Climate Initiative (TCI), a cap-and-invest program designed to cut carbon emissions and generate money for clean-transportation projects in 10 Northeastern states.

Modeled loosely on RGGI, the initiative called for a limit on transportation-sector carbon-dioxide emissions and required wholesale transportation-fuel suppliers to buy allowances corresponding to the emissions produced by gasoline and diesel fuel covered by the cap. Proceeds from auctions of these allowances would fund clean-transportation priorities at each state’s discretion, with the possibilities theoretically ranging from public transit projects to wireless-internet improvements aimed at promoting teleworking.

Developed over years, the initiative foundered in 2021, when governors in the Northeast walked away from commitments they had made to carry it out. The problem was not solely the intense and predictable opposition from the fossil fuel industry. The initiative also received pushback from environmental justice advocacy groups concerned that minority and low-income communities had not played a substantive role in the program’s design.

Although some environmental justice groups ultimately did embrace TCI, others warned it would burden low-income communities with a regressive tax by causing fuel-price increases. They also asserted that the auctioning of allowances would not guarantee a reduction of tailpipe emissions in communities bearing the brunt of such pollution.

In December 2020, 10 environmental justice advocacy groups from around the country declared their opposition to TCI, saying steps to protect communities vulnerable to tailpipe emissions should have been central to the initiative but were not. “These communities should not have to settle for whatever incidental reductions are achieved by carbon trading or reductions that are highly uncertain because they are to be produced by policies that have not been fully developed,” their statement read in part. “We owe these communities more.”

(Reuters/Bob Strong, Denmark)

Looking back, TCI’s supporters—state government officials, advocacy groups, and funders included—recognized they had not engaged early enough with environmental justice organizations to ensure sufficient participation on their part in shaping the initiative. But despite this missed opportunity and other reversals, clean-transportation work had expanded dramatically in New England and beyond by the end of our spendout period, as had the depth and breadth of the advocacy network powering it. New England states ranked among the top U.S. states in electric-vehicle adoption, with Vermont placing second in charging stations per capita and Massachusetts among the top 10 in electric-vehicle purchases.

Blueprints for the future

Arguably the crystallization of our grantees’ diverse efforts over the years was their advocacy for state climate mandates. Known as Global Warming Solutions Acts (GWSAs), these measures establish greenhouse gas emissions targets and require states to formulate climate action plans for meeting them. Thanks to the successful campaigns for advances such as net metering, renewable portfolio standards, efficiency programs, and clean power development, advocates were able to point to powerful tools that states could use to meet these commitments.

As of 2021 our grantees and partner organizations had successfully pushed every state in New England except New Hampshire to pass climate mandates, which in each case require progressively greater emissions reductions by 2030 and 2050. And as we closed our doors, all of these states had begun work on their climate action plans.

The mandates, in some cases strengthened by legislation states passed after approving their GWSAs, are ambitious. Massachusetts and Rhode Island committed to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Connecticut required a zero-carbon electricity supply by 2040 and overall carbon emissions 80% below 2001 levels by 2050. And Maine and Vermont each approved legislation mandating economy-wide carbon emissions to be cut to 1990 levels by 2050.

The grantees heading the GWSA effort included the Mass Power Forward coalition and CLF in Massachusetts, and, in Maine, the Natural Resources Council of Maine. In Vermont, Energy Action Network, Vermont Natural Resources Council, and Vermont Public Interest Research Education Fund led the way. Green Energy Consumers Alliance spearheaded the work in Rhode Island, while the Connecticut Roundtable on Climate and Jobs and Save the Sound did so in Connecticut.

These organizations, drawing on previous climate-policy roadmap work led by Acadia Center, CLF, and Energy Action Network, assisted state lawmakers in designing the state-by-state mandates. They also helped build public support for these mandates and served on advisory councils formed to ensure that the GWSAs would spawn well-implemented policies.

As in other initiatives ranging from gas-infrastructure opposition to electrification of transportation, our grantees brought increasingly sophisticated technical expertise and grassroots organizational power to bear, providing important new dimensions to New England climate and energy advocacy. When our program concluded in 2021, we looked back with wonder and pride at the scope of this advocacy. Over the decades, our grantee partners had addressed one after another critical aspect of the region’s complex climate and energy challenge.

“If you think of JMF’s climate and clean energy program as having a footprint, you’d have to call it a Triple E,” said Ruth Hennig, our former executive director. “If a strategy failed, we worked to understand the reason and modified the program to produce better results. We trusted our grantees and worked with them to make necessary strategic adjustments, an approach that led to progress on an impressive variety of fronts. Of all the things that JMF accomplished, New England’s growing regional leadership in modeling meaningful climate and energy policies is the one that makes me proudest.”