Our Founder

Table of Contents

In John Merck Fund board sessions over the years, remarks such as “May would have loved this” or “I wonder what May would’ve thought about that?” more than occasionally cropped up in conversation around the meeting table.

“May” was the family nickname for Serena Merck, who founded the Fund in 1970 in tribute to her then 40-year-old son John. The second of three children born to Serena and her husband, George Merck, president of the U.S. drug company Merck & Co., John had battled severe intellectual disability and epilepsy since early childhood.

For relatives of hers who served as Fund trustees following her death in 1985, Serena Merck was rarely far from mind during key decision-making junctures. This presence stemmed partly from memories of her keen personal commitment to the Fund’s original mission: to improve care and therapy for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. But it also had to do with the nature of Serena Merck herself: a compassionate, refreshingly irreverent woman who, though married to one of the country’s leading industrialists, was thoroughly unpretentious and unflaggingly kind to all.

Her highest praise for others was often to say that they were “doing such good.” She might as well have been describing herself. Her son-in-law Frederick Buechner once wrote that Serena Merck was “not only a great lady, which is one thing, but also a good woman, which is another.”

New Jersey childhood

Serena Merck began her life as Serena Stevens in 1898 in suburban Summit, New Jersey, the second of four children born to Josephine Stevens and her husband, George, an insurance executive. The family lived on Waldron Avenue, in a neighborhood Serena described as comfortable and safe, yet freewheeling, with children racing from one house to another in packs.

Her love of good-natured competition and debate likely dated from those years, as did a sense of humor that tended toward the slapstick—possibly thanks to her prankster father. Among her favorite memories were family “fire drills” in which George Stevens had his children toss clothing from a second-story window and then hurry down a ladder to the ground, where he’d spray them with a garden hose for effect.

In later years she would occasionally let slip that as a teen she played a mean center on her school basketball team, even though her admission would risk raising a subject she found embarrassing: her considerable height. How tall, exactly? “Five-twelve,” she’d answer if pressed, through a smile equal parts sheepish and playful.

Stimulating as her early life apparently was, it was not insulated from the turmoil of the new century. She herself helped see to that. In her late teens and early 20s during World War I and the Great Influenza, she served as a hospital volunteer in New York City, providing nonprofessional assistance to patients and staff amid the period’s ongoing shortages of trained home-front nurses.

Though she was rarely one to boast, her references to this work in future years revealed her considerable pride in it. So, too, did her lifelong safekeeping of the gray uniform she had worn during her hospital shifts.

Wife and mother

Serena Stevens married George Merck in 1926. He had recently succeeded his father as president of Merck & Co. Inc., the American offshoot of a pharmaceutical dynasty founded in Darmstadt, Germany, by Friedrich Jacob Merck in 1668. It was his second marriage. His first, in 1917, had ended in divorce.

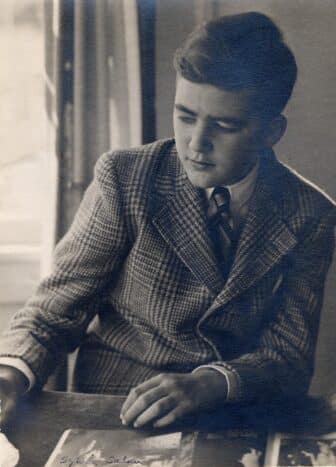

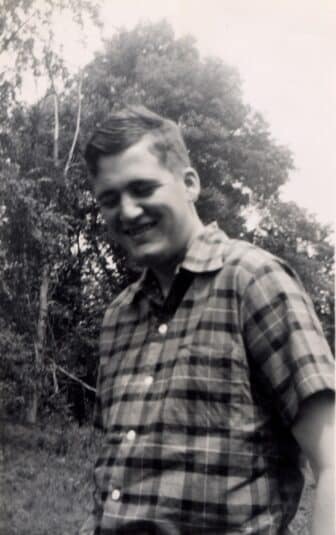

John Merck was born on Christmas Day of 1929. He developed normally into toddlerhood, but then began having epileptic seizures and deepening intellectual, emotional, and physical challenges that would leave him severely disabled throughout his life.

and son John

The problems were attributed to brain damage from meningoencephalitis—an inflammation of the brain and protective tissue around it that is usually triggered by a virus, bacteria, parasite, or other microorganism, but whose cause was not known in John’s case.

John’s older sister, Serena, nicknamed “Bambi,” remembered her little brother in his early years as a lively, mischievous boy racing around in a pedal car on the family’s driveway in West Orange, New Jersey. She recalled that sometimes he would suddenly grow frightened and pale, and would say, “Oh no, it’s coming,” shortly before being gripped by one of his seizures. “Johnny was going to be perfect, then he got worse and worse,” she said in 2022. “The [seizures] he had were awful.”

Serena Merck was mindful how lucky she and her husband were to face this challenge with the resources they had at hand. They could afford care and supervision for John, and, as he grew older, they could arrange to have him live nearby, staying in close touch with him while continuing to pursue their own lives.

Although some families of that time kept members with developmental disabilities effectively shut away, Serena Merck remained a constant, central presence in John’s life, doing all she could to see to his health and happiness.

She also ensured that he had contact with visiting family, whether at Eagleridge, her and George Merck’s estate in West Orange, or at their vacation houses in Rupert, Vermont, or Hobe Sound, Florida.

Her grandchildren remember playing a form of catch with John as he sat in his wheelchair during outdoor Sunday lunches in these settings, and they recall seeing the delight in their grandmother’s eyes whenever she successfully coaxed John to smile.

As in other families facing similar situations, John’s struggles and the attention required to address them posed challenges not only for Serena Merck, but also for her and George Merck’s two daughters—Bambi and Judy.

George Merck’s ability to ease such pressures directly was limited at best, given his colossally busy work life. Serena Merck divided her efforts as well as she could, while preserving some time for friends and for activities including golf, bridge, painting, and charitable work.

Her daughter Judy, in a recollection written in 2022, said that although Serena Merck was “mostly occupied with Johnny” during her childhood, she nevertheless experienced her mother as a “rock, protector, advocate.”

Different learners

The creation of The John Merck Fund represented Serena Merck’s second major philanthropic effort to address developmental disabilities. Her first, begun decades earlier, was to help establish Maplebrook, a boarding school in Amenia, New York, that has served children with learning disabilities for more than 75 years.

When she co-founded Maplebrook in 1945, she hoped it would accommodate John, then a teenager. This, though, was not to be. It eventually became clear that John’s medical problems were growing too severe to be addressed by the school, which in a 2017 published history described its students as “youngsters who learn differently and might also possess physical handicaps.”

Still, Serena Merck served Maplebrook for much of the rest of her life, not only remaining one of its foremost funders, but also playing an important part in its governance. School records show that while still serving as a trustee little more than a decade before her death, she was a member of the Maplebrook board’s finance and planning committee and an alternate on its executive committee.

“Mrs. Merck was a grand lady,” Lon Adams, who headed Maplebrook School from 1974 to 1989, commented for this history in 2022. “She had a quiet nature, but was not afraid to give her opinion when solicited. … She continued as a major supporter throughout her life and was active on the board for many years.”

Launching JMF

By the time she founded The John Merck Fund in 1970, Serena Merck was over 70 years old, her husband, George, had died more than a decade earlier, and their son, John, was 40. There was little probability or expectation that the work of the Fund would benefit John, who would live until 2001, though she felt it important that the foundation carry his name. Her hope instead was to use the Fund to improve care and therapy for children afflicted by developmental disabilities, with the aim of bettering not only their lives, but also those of their family members.

Initially, she worked to support the vision of Irene Jakab, a psychiatrist who was on staff at McLean Hospital, a psychiatric teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School, and later became a professor at the University of Pittsburgh. Jakab, who oversaw John Merck’s care for many years, helped establish that a large subset of children with developmental disabilities had co-occurring neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders and should be—but at that time were not—treated for both.

Backing Irene Jakab’s work was the first in a succession of strategies that the Fund pursued during its more than 50-year history to improve prospects for those with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

After Serena Merck died in 1985 at the age of 86, an infusion of new assets from her estate allowed the Fund to support work in additional subject areas ranging from clean energy development to New England farmland preservation.

It’s a tribute to Serena Merck that in discussion of those subject areas, too, her family members serving on the board would not infrequently ask themselves or each other: “What would May think?”