Job Opportunities Grantmaking

Table of Contents

(Vermont Works for Women)

Sometimes our “Dare to fail” mantra inspired us to enter undeniably vast and complex issue areas fully recognizing that progress would be hard to foster, given the scope of the challenge and the limited resources we could bring to bear. Such was the case with our job opportunities grantmaking, which we launched in 1994 in hopes of helping low-income people get and retain steady jobs—largely in urban areas, but in rural settings as well.

From the start, there were differences of opinion on what the best strategy would be. There also were concerns that the job-access bottlenecks being addressed were too large and complicated for a small foundation to tackle and that the effects of our efforts would be difficult to track.

But a number of our trustees felt strongly that with so much of our grantmaking targeting environmental protection and developmental disabilities, the foundation ought to help people struggling to find steady employment. These trustees included new third-generation family board members as well as “friend” trustees such as Arnold Hiatt, who championed corporate engagement in the improvement of urban social conditions while president of the Stride Rite footwear company from 1968 to 1992.

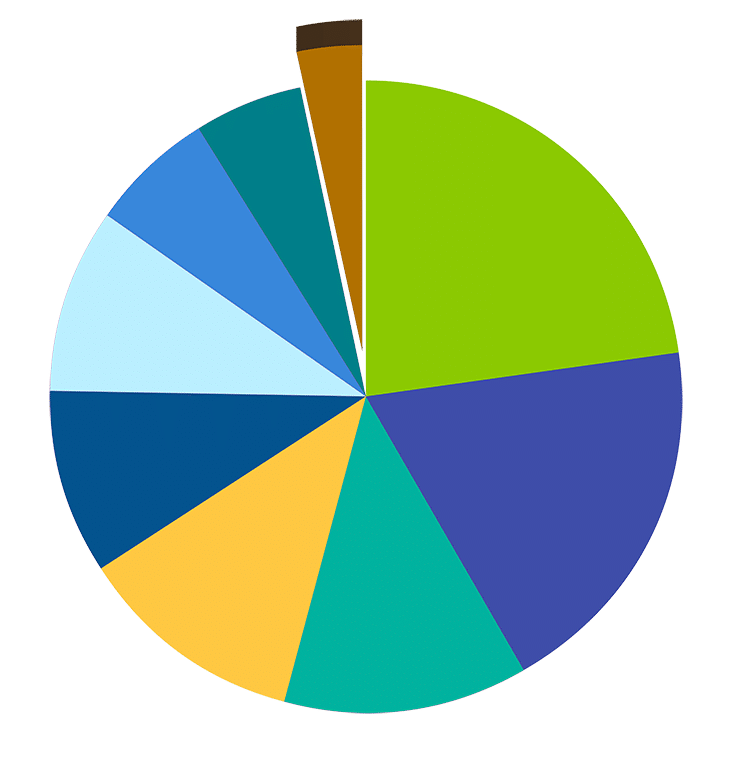

JMF Grants 1994-2009: Job Opportunities

Total $ Amount

$9,912,300

Years of Program

1994-2009

# of Grants

247

Broad focus at first

We ultimately decided to create a program focused on job creation and individual income generation at the community level rather than on a state or regional scale. Initially, our program targeted low-income communities in the Northeast and mid-Atlantic states, with grants earmarked for job training, business incubation, and microentrepreneurship. Grants for business incubation went mainly to help develop model employee-owned ventures in temporary-employment services, home healthcare, and childcare. And in the case of microenterprises, our assistance took the form of grants, loans, and technical assistance support.

Following a program review in 2000, the geographic focus of our job opportunities grantmaking was narrowed to New York City and New England in order to concentrate and more easily evaluate our efforts. For these and other reasons, the range of funded activities narrowed as well. The review noted that an economic downturn in the 1990s had taken a heavy toll on startups supported through our business-incubation grants, with Medicare reimbursement changes exacerbating the challenge for home-healthcare ventures. The assessment also observed that the effectiveness of grants and loans for microentrepreneurs had proven difficult to measure.

Conducted during a yearlong program hiatus, the review concluded that although our grants had helped boost individuals’ income-earning ability, changes in the workplace and policy landscape had significantly reduced the possibility of spurring broader, systemic change through grantmaking. It recommended we make more strategic use of our resources by addressing funding gaps facing job training programs and by building the ability of training practitioners to adapt to new public funding and policy conditions.

training session.

(Year Up)

We concentrated funding for job training on pilot initiatives, especially those developed for marginalized populations such as ex-offenders, women, refugees, the recently homeless, and young adults not attached to school or the workforce. For instance, some of this support went to Boston-based Year Up, an intensive information-technology education and apprenticeship program, as it replicated its model in Providence, Rhode Island, and in New York City. We also helped fund a unique model, created by the Center for Employment Opportunities in New York City, that placed ex-offenders in subsidized jobs immediately after release and helped them transition to permanent employment.

First Step model

Still other JMF grants complemented pioneering work done by the organization Common Ground and its founder, Rosanne Haggerty, to rehabilitate historic buildings in New York City and convert them into mixed-income housing that included units for people who are homeless. Our grant support, which began in 1996 and continued to 2003, helped Common Ground—later renamed Breaking Ground—launch a new housing model inspired by surveys of unhoused people on the specifics of the challenges keeping them on the street.

“The concept, one of the best ideas we’ve acted on, came from individuals who told us there was no way for them to move off the street on their own terms into basic accommodations that offered a private, clean, and safe place to stay for a modest amount on a pay-by-the-night, or week, basis,” Haggerty recalled for this history in 2023. “Our permanent supportive housing units required a lease, a stable income, and we and others had not seen those requirements as the barriers they are.”

The new First Step Housing model, piloted at The Andrews, a former lodging house on the Bowery that had been thoroughly renovated by Common Ground, helped provide “short-stay” accommodations of a type that had become ever-scarcer since the 1950s. Unhoused people were taken in off the street to stay in The Andrews’ cubicle-style units while receiving help to overcome their longer-term employment and housing challenges.

“In previous eras, places like rooming housing or YMCAs provided an option like first-step housing, but those very basic options have disappeared,” Haggerty said. “With JMF’s help we were able to recreate a missing form of housing, designed with the input of those experiencing homelessness.”

(Alan Shindler)

Rural programs, too

JMF job opportunities grantees worked in rural settings as well. Among them was Vermont Works for Women, whose trade-skills education and training in after-school programs, prisons, and other venues put thousands of women and girls onto the path of economic independence. Another, ReCycle North (later named ReSOURCE), helped Vermont at-risk youth and low-income adults acquire job skills through the repair and resale of household items that otherwise would be discarded.

Tiffany Bluemle, executive director of Vermont Works for Women from 2003 to 2015, wrote in 2021 that the fruits of her organization’s collaboration with JMF went well beyond grant support. Particularly useful, she wrote, was the encouragement, flexibility, and commitment provided for years by JMF board chair Frank Hatch and Rowan Murphy, the Fund’s job opportunities grantmaking consultant.

“It’s no exaggeration to say that The John Merck Fund played a pivotal role in expanding the scope and impact of our work with women and girls in Vermont at a time when similar organizations across the country were forced to close their doors,” wrote Bluemle, who won election to the Vermont State House of Representatives in 2020. “Its financial support was important, certainly. But the Fund’s greatest contributions to Vermont Works for Women were perhaps less tangible. It offered us thought partners in Frank Hatch and Rowan Murphy, who were interested not only in what we had done, but in what we had learned. They challenged us to think expansively and to name what we needed to get there. Because the Fund invested in our work, state agencies were persuaded to follow suit. It gave us street cred—and confidence.”

Funding for microenterprises resumed after the program review, but no longer in the form of grants and loans to help these businesses build their financial resources. Instead, we devoted our support in this area solely to organizations providing technical assistance to microentrepreneurs. Among these grantees was the Center for Women & Enterprise, which brought peer counseling, mentoring, and other assistance to bear across New England—largely on behalf of low-income women entrepreneurs, and especially those who were minorities and single mothers.

The revised program guidelines also allowed for support of a limited number of field-building initiatives to train workforce-development providers, improve service models, share best practices, and engage in advocacy and policy development. Grantees supported in this work included the New York City Employment and Training Coalition, Boston’s SkillWorks, and the National Skills Coalition’s work with New England providers.

(ReSOURCE)

The job opportunities program was eliminated along with two other programs in 2009 as the foundation began concentrating its resources on four core programs that eventually became the focus of our 10-year spendout. Though questions about how to optimize grantmaking strategy and impact had persisted throughout the program’s lifespan, our job opportunities support for more than 100 training organizations, microenterprise support centers, and workforce intermediaries created employment and entrepreneurial possibilities for thousands of people.

More broadly, our exceptional grantees created new programming that practitioners in other communities adopted and cloned around the region.

“The John Merck Fund was an early supporter of Year Up and our efforts to connect deserving young adults to meaningful careers,” said Gerald Chertavian, CEO of Year Up. “[JMF’s] continued support enabled Year Up to scale and broaden our impact, and we’ve since served over 36,000 young people while working with some of the nation’s largest employers to redefine where talent comes from and to transform hiring practices.”