Human Rights Grantmaking

Table of Contents

(Maria Rocío de la Torre/Shutterstock)

The John Merck Fund entered the human rights field in tribute to Orville Schell, a distinguished New York City lawyer who championed human rights worldwide and chaired the Fund from its inception in 1970 until his death in 1987. We established our human rights program shortly after he died, with the earliest grants including a 1988 contribution to help create the Schell Center for International Human Rights at Yale Law School.

From 1988 through 2001, our program supported a wide variety of projects to document human rights violations and promote the rule of law, train human rights lawyers, and protect threatened advocates. There were no particular geographical boundaries in this period, with projects addressing rights conditions in Algeria, Burma, Chechnya, China, Egypt, Gambia, Israel, Northern Ireland, Russia, and Turkey, as well as a few countries in Latin America, including Argentina, Colombia, and Mexico.

Among the grantees were three U.S.-based groups—Human Rights Watch, Physicians for Human Rights, and the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, later named Human Rights First. Early grantees also included frontline groups abroad. A notable example was the Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense (in English, the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team; EAAF), an Argentine scientific nonprofit that used archeological techniques to excavate mass graves and accumulate evidence for human rights litigation in Argentina and eventually other countries around the world.

(EAAF)

“The John Merck Fund was among the first funders of EAAF’s international work outside of Argentina, enabling us to work throughout Latin America and in numerous countries in Africa, Asia, and Europe,” Mercedes Doretti, the group’s co-founder and director for its North and Central America programs, said in 2022. “With the Fund’s help, we grew to work in more than 60 countries to provide truth for over several thousand families seeking their missing loved ones, train thousands in and out of government in forensic best practices, and supply forensic evidence to court cases and international tribunals that imprisoned dictators and senior military officers in 10 countries for crimes against humanity. The vision [JMF] saw in us early on made possible a greater impact than we ever imagined upon our founding in 1984.”

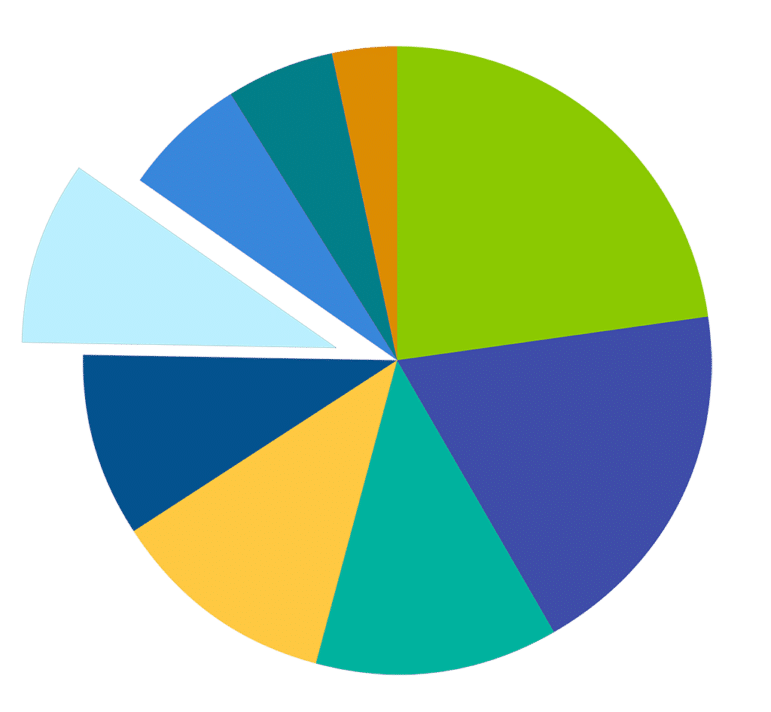

JMF Grants 1987-2009: Human Rights

Total $ Amount

$28,270,380

Years of Program

1987-2009

# of Grants

706

Focus on Latin America

In 2001 our board decided to give the program greater focus by concentrating the bulk of our human rights grantmaking on Latin America. As a first step, we hired consultant Juan Méndez to design and help oversee a grantmaking strategy that could contribute to rights advances in multiple countries. It was a tall order, given the highly varied nation-by-nation contexts in a region still struggling to emerge from years of political violence and dictatorship.

But Méndez, who had been tortured and imprisoned by Argentina’s right-wing military government in the 1970s for providing legal representation to political prisoners, brought a wealth of human rights knowledge and experience to bear. He had held leadership posts at Human Rights Watch, the Inter-American Institute of Human Rights, the University of Notre Dame’s Klau Institute for Civil and Human Rights, and the International Center for Transitional Justice.

With Méndez’s guidance, our human rights grantmaking provided direct support to frontline organizations in six Latin American countries that were selected to reflect three distinct sets of circumstances then evident in the region:

- Colombia and Mexico, where extreme political violence or armed conflict was occurring;

- Peru and Venezuela, where democratic processes were overlain with authoritarian leadership; and

- Argentina and Chile, two democracies with potential for significant civil-society development.

Grantmaking was tailored to help the most advanced countries serve as rights-protection exemplars and to help those countries that were less advanced make tangible progress.

In the countries with extreme violence, projects included the documentation of rights violations and the use of international courts to press for protections. Among the groups we helped engage in this work was Tlachinollán Human Rights Center in the state of Guerrero, Mexico. After receiving Fund support in its early stages, Tlachinollán became a leader of rights advocacy in that rural state. It spotlighted violations ranging from the sale of indigenous girls in arranged marriages to the 2014 kidnapping and disappearance in Guerrero of 43 trainee teachers active in social advocacy, a largely unresolved case that fueled ongoing accusations of state complicity.

The Colombian Commission of Jurists (CCJ), meanwhile, launched strategic litigation in domestic and international tribunals with JMF’s help to safeguard rights amid Colombia’s brutal civil war. CCJ has successfully sought prosecution of human rights abusers in cases involving forced disappearance, murder, and crimes against humanity.

In ostensibly democratic countries with authoritarian leadership, our grantees promoted human rights awareness and defended rights campaigners. In Peru, for instance, the Pro Human Rights Association (Aprodeh) worked on various fronts to restore protections tattered during the 1990–2000 presidency of Alberto Fujimori, whose police committed widespread abuses including illegal arrests, torture, and infiltration of opposition political parties. And our grantee Venezuelan Education-Action Program on Human Rights (Provea) promoted the defense of civil liberties as the populist government of then-President Hugo Chávez took an increasingly aggressive authoritarian turn.

And in countries with strong prospects for civil-society development, JMF grants supported precedent-setting litigation and policy work. Among our core grantees involved in this activity was the Center for Legal and Social Studies in Argentina, which used the courts and public education campaigns to spur initiatives including police and prison reform. In Chile, we supported the work of the University of Chile Human Rights Center, which had been co-founded by renowned human rights advocate José Zalaquett after his forced exile from Chile during the dictatorship of Gen. Augusto Pinochet.

Longstanding U.S. partners

Even after Latin America became the program’s primary focus, we continued making grants to the three U.S.-based groups we’d supported since the early days of our Human Rights Program: Human Rights Watch, Human Rights First, and Physicians for Human Rights.

This funding to longtime U.S. partners included emergency grants to help Human Rights Watch assist advocates who found themselves in immediate danger—a total of 64 grants amounting to $420,000 over the years. And in the aftermath of 9/11, we helped fund Human Rights First’s “End Torture Now” campaign challenging the systematic use of torture under the George W. Bush administration in the interrogation of terrorism suspects. Conducted under longtime Human Rights First executive director Michael Posner, the campaign assembled a nonpartisan group of retired generals and admirals who spoke out powerfully against U.S. government-sanctioned torture, which the Bush administration described as “enhanced interrogation.”

The combination of institutional support and quick-turnaround funding for time-sensitive initiatives helped all these groups as they became leaders in the human rights field.

“The John Merck Fund was one of the first foundations to believe in Human Rights Watch at a time when the organization was tiny and the human rights cause was in its infancy,” longtime Human Rights Watch executive director Ken Roth said shortly before stepping down in 2022, having headed the organization for 29 years. “And for more than a decade, the Fund enabled Human Rights Watch to assist dozens of human rights defenders who were at risk, facing serious threats to their personal safety because of their human rights activism.”

Evolving field

Our human rights grantmaking occurred in a context of growing breadth and complexity in the international human rights advocacy field. Relatively small, narrowly focused U.S.-based groups became larger and more sophisticated. They began documenting working conditions in offshore factories that supplied transnational retailers; integrating human rights and environmental protection in defense of indigenous communities; and challenging violations of constitutionally guaranteed rights to social services.

In Latin America, rights defenders—some of them JMF grantees—also advanced notably in their capabilities and reach despite the fact that human rights progress in the region remained uneven. These organizations made increasingly effective use of public advocacy and litigation to defend and, where possible, expand civil liberties, weighing in on issues ranging from police abuse and prison conditions to indigenous land rights. They also launched pioneering efforts to assert economic, social, and cultural rights.

Encouraging as these gains were, our human rights program was one of two grantmaking areas eliminated in 2009 when we narrowed our focus to boost our impact in four core issue areas—climate and energy, developmental disabilities, farm and food systems, and health and environment. Though our human rights grantmaking ended, we look back with pride and admiration at the contributions our U.S. and Latin American grantees made to the field, to their target countries and—by way of example—to the world.

(American University Washington College of Law)

For Juan Méndez, at the time of our spendout a professor of human rights law in residence at American University’s Washington College of Law, the growth and ongoing influence of our in-region partners was particularly noteworthy.

“The nongovernmental organizations that JMF supported in Argentina, Chile, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, and Mexico thrived in those years in which JMF was key to their sustainability, and it is gratifying to see that in all cases they have continued to make a huge difference in human rights, even as the challenges and pitfalls shifted in each country over the years,” Méndez said in 2022. “All of them continue today to stand out as the most effective monitors of human rights developments, proponents of public policy, and defenders of equality and justice in the region.”