Reproductive Rights Grantmaking

Table of Contents

(@ Alicia Armijo/ZUMA Press Wire)

Virtually all of our programs adjusted their approaches over the years in response to challenges and opportunities, but perhaps none did so as persistently and creatively as our reproductive rights grantmaking.

Initially part of an effort begun in 1987 to advance global population sustainability, within a decade our reproductive health and rights grantmaking had become a stand-alone, U.S.-focused program that supported work on a range of objectives. These objectives included improving access to abortion and contraceptive services, providing training for reproductive health professionals in the provision of these services, defending the legal right to abortion, and expanding medical options for abortion and contraception.

The multiple approaches and experimentation we employed over the years reflected the complexities of one of the most divisive social and political issues of our time. Hard ideological positioning on both sides of the abortion debate made it exceedingly difficult to advance reasoned discussion, much less to achieve wise and balanced policy.

Yet despite these challenges, we were able to help extraordinary advocates develop specific competencies that—while not definitive tide-turners in the larger struggle—provided critical tools for the ongoing pro-choice movement. Among these leaders were Marie Bass of the Reproductive Health Technologies Project, Janet Benshoof of the Center for Reproductive Rights, and Eleanor Smeal of the Feminist Majority Foundation.

We set two goals when we established our population policy program in 1987: first, to help slow what many experts viewed as unsustainable population growth in developing countries, and second, to defend the legal right to abortion in the United States. But by 1997 our board had decided to end population-policy funding and to instead devote those resources to a freestanding U.S. reproductive health and rights program.

The reasons for the shift were at once practical and profound. Our board shared experts’ long-standing concerns that a projected world population of up to 14 billion people would exceed the earth’s carrying capacity, exhausting food and water supplies, straining national economies and social services, and destroying ecosystems. But in a practical vein, we realized through experience that we lacked the funding capacity and in-house expertise needed for effective grantmaking in a field as sprawling as population policy. We also came to embrace the view that a Western philanthropic focus on population control in developing countries was too narrow and, worse, hypocritical.

Debate on the global population-control question raged in the late 1980s and early 1990s in the fields of women’s rights, international development, family planning, and environmental protection. Health and rights advocates argued that as women in developing countries attained more autonomy thanks to better education, greater economic independence, and control over their own reproductive lives, they would decide independently to have smaller families. At the same time, women’s groups in the Global South pointed out that with per capita consumption in the West far exceeding consumption in the developing world, Western organizations were in a poor position to push for population reductions overseas.

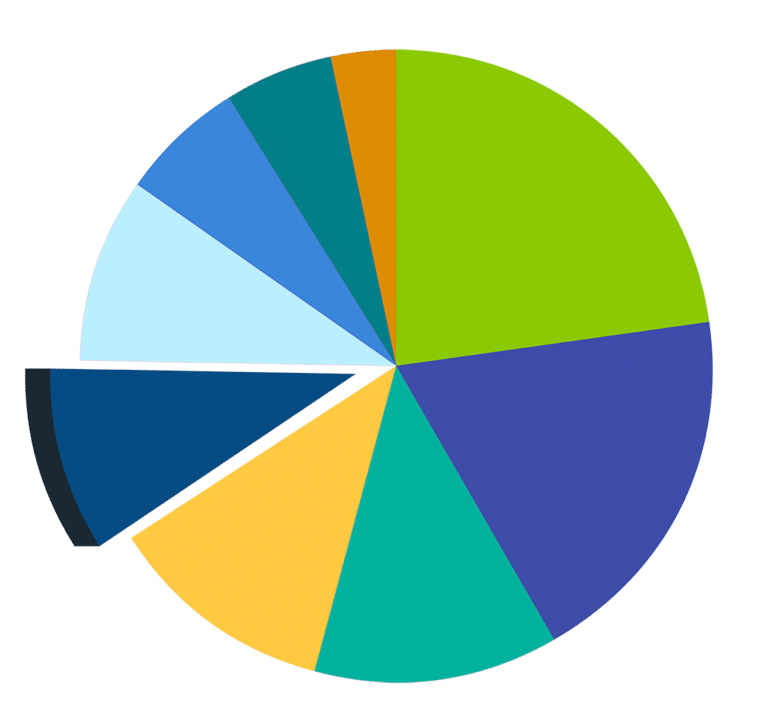

JMF Grants 1987-2009: Reproductive Rights

Total $ Amount

$28,400,834

Years of Program

1987-2009

# of Grants

538

Equity…and security

The reproductive health and rights program we eventually launched emphasized equity. Specifically, it sought to support advocacy based on the principle that all women in the United States should have access to high-quality reproductive health services, a goal that was becoming increasingly difficult to attain.

The cumulative impact of stronger anti-abortion advocacy, the “graying” of the abortion-rights movement, and increased use of fetal ultrasounds in early pregnancy put abortion-rights advocates in a defensive position. Amid this complex and often hostile environment, we backed projects to boost public abortion-rights support by refining the messages advocates used.

across the country following the announcement

of the Dobbs decision.

(Longfin Media/Alamy Stock Photo)

At the same time, we put our nimble grantmaking capabilities to the test by assisting grantees as they responded in real time to violence visited on abortion providers and clinics in the early 1990s. Within days of attacks in 1994 that left two abortion clinic workers dead in Brookline, Massachusetts, for instance, we helped reproductive-rights advocacy leaders launch a national collaborative effort to defend embattled clinics and improve security for workers and buildings.

Using a multi-year grant from The John Merck Fund, three groups—the Feminist Majority Foundation, Planned Parenthood Federation of America, and the National Abortion Federation—collectively bolstered security procedures and systems, and provided training for federal and local law enforcement officials. Thanks to efforts such as these, harassment and attacks by abortion opponents declined substantially.

Multiple paths

Looking to make a difference in other ways, we focused program resources on removing the need for abortion, mainly by funding initiatives aimed at reducing unintended pregnancies through support for improved comprehensive sexuality education and access to contraceptives. We also sought to help expand the use of promising new technologies capable of preventing pregnancy and terminating unintended pregnancies.

In 1990, we became an early co-funder of a campaign by the Feminist Majority Foundation to allow the sale in the United States of mifepristone, or RU-486, a drug developed in France to provide women there a nonsurgical means of medical abortion. After eventually winning U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval in 2000, the drug—administered in combination with misoprostol—became widely used across the country, accounting for over half of U.S. abortions by 2020.

(Shutterstock)

The Fund also supported numerous early efforts in the 1990s to build awareness and use of postcoital birth control called emergency contraception (EC). Among these initiatives was a project spearheaded by the Feminist Majority Foundation that created the first national toll-free hotline where callers could obtain information about local EC providers.

Trial and error

As in some of our other program areas, we worked to help grantees build their communications capability and effectiveness. Unfortunately, two significant efforts on that score did not bear fruit in our reproductive rights grantmaking.

The first involved the development of a centralized communications capability akin to one that environmentalists had created through the National Environmental Trust. The initiative foundered, however, largely because advocacy groups resisted taking a common approach, prompting potential co-funders to withdraw their support.

A second, complementary effort to develop a common communications strategy stalled as well. It had been hoped that coordinated messaging could more effectively illuminate the full agenda of the anti-abortion movement—making clear, for instance, that so-called right-to-life advocates aimed to block women’s access not only to abortion, but also to birth control.

But polling we commissioned showed prohibitively strong public disbelief that abortion opponents would have such aims. We concluded that it would be beyond The John Merck Fund’s capability to provide the scale of support needed for grantees to change the narrative.

By 2001, we had stopped funding projects aimed at changing public opinion on abortion. Though we continued our abortion-services funding, we earmarked it for training abortion providers in first-trimester surgical abortion, for furthering medical abortion with mifepristone, and for preserving abortion services in full-spectrum healthcare settings such as health maintenance organizations.

In 2009, we discontinued our reproductive rights grantmaking altogether as part of an effort to concentrate our funding in four issue areas—climate and energy, developmental disabilities, farm and food systems, and health and environment.

Staying power

Over the previous two decades, the Fund, its allied funders, and our grantee partners clearly had not managed to defuse the conflict over abortion. But we could take pride in having helped pro-choice advocates continue to courageously defend abortion rights in the face of implacable, sometimes violent opposition.

That opposition culminated in a legal sense on June 24, 2022, when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the high court decision that had provided the framework for abortion rights nationally since 1973. In explicitly ending federal constitutional protections for abortion, the high court diminished women’s rights and threatened women’s access to reproductive healthcare.

But the ruling also drew wide criticism, revealing a deep reservoir of support for abortion rights. An unequivocal expression of that support came on August 2, 2022, when voters in politically conservative Kansas decisively rejected a state constitutional amendment that would have allowed state legislators to capitalize on the removal of federal protections by enacting far-reaching abortion restrictions.

Far from feeling despondent, many abortion-rights advocates were confident that grassroots efforts to guarantee women’s reproductive-health access and decision-making would grow and eventually prevail, energized by public reaction to the Dobbs decision.

(Courtesy of the Feminist Majority Foundation)

“We have the overwhelming majority of this country and the world on our side, and I have no doubt reproductive health advances will continue,” Eleanor Smeal, president and co-founder of the Feminist Majority Foundation, commented for this history in 2022. “We had a well-funded and violent opposition. People thought we were crying wolf. Now they know that a right can be taken away. It’s a sad thing we’ve had to have this struggle, but people want scientific advances and better public health, especially the young. [Anti-choice activists] will not stop the march of history.”