Our Approach

Table of Contents

from 1987 to 2006

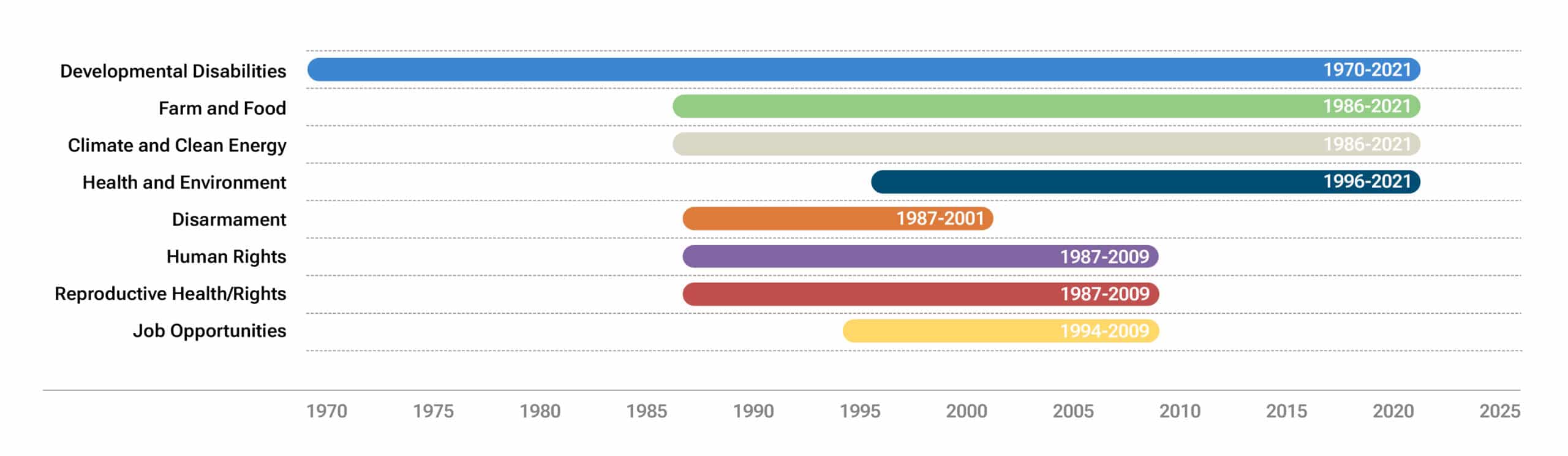

The John Merck Fund began its work in 1970, during the Vietnam War and the U.S. presidency of Richard Nixon. By the time we had made our last grant—nine presidents and more than 50 years later—Joe Biden occupied the White House and the world was grappling with a pandemic, resurgent authoritarianism, and the intensifying effects of global warming.

Organizational change wouldn’t be surprising over a period so lengthy and fraught, and during our journey we did, in fact, navigate three distinct grantmaking chapters. These began with a 15-year stretch in which our founder, Serena Merck, and a small board pursued our lone goal at the time: to foster better care and treatment for children with developmental disorders.

Following Serena Merck’s death in 1985, her son-in-law and our longtime board chair, Frank Hatch, led the foundation into various additional issue areas, several of which—climate protection, reproductive rights, and international human rights among them—carried a progressive-advocacy edge.

The final chapter began in 2012, six years after the Fund had come under its third generation of leadership. That’s when we launched a 10-year spendout that focused on four core grantmaking areas—developmental disabilities, climate and energy, environmental health, and the New England regional food system.

Though we adjusted our sights and strategies from stage to stage, our philanthropic approach in key respects remained the same. As a relatively small foundation, we always saw our niche as a provider of speedy and nimble support for potentially mold-breaking initiatives. Bigger funders could make far heftier grants, but they also could be slow-moving, rigid, and risk-averse, overseen as they often were by large staffs and populous boards whose meetings were few and far between.

We sought as much as possible to help changemakers who—due to their young age, the unorthodoxy of their approach or both—were not yet, as an internal Fund document put it, “bathed in the aura of funding respectability.” And when needed, we tried to serve grantees as active thought partners, mulling next steps with them and helping them develop not only their work, but also their capabilities.

This approach, and the family philanthropic culture that informed it, ensured a certain continuity in JMF’s structure, governance, and mindset. Though we experienced periods of growth as our investment and program portfolios expanded, we maintained a small, low-key board of family and nonfamily “friend” trustees who worked closely and collegially with a lean team of staff and consultants.

Perhaps most importantly, we gladly took risks in order to make the greatest difference possible—an attitude that spawned the informal in-house mantra: “Dare to fail.”

Philanthropic backdrop

Our approach to grantmaking was partly a matter of necessity. Compared with large foundations capable of dispensing $500 million to $1 billion per year with individual grants routinely in excess of $250,000, The John Merck Fund occupied the small-to-medium end of the spectrum. Our grants usually ranged from $50,000 to $100,000, and by far the highest annual grantmaking total we ever registered was $16 million, in 2007, with $11 million being more typical when we had a multi-program portfolio.

But temperament played a role, too. Much of the Merck family’s philanthropy was characterized by hands-on engagement with an emphasis on achieving impact and a willingness to go out on a limb.

Serena Merck’s husband, pharmaceutical executive George Merck, demonstrated this approach by acquiring 2,000 acres of land in southwestern Vermont and, in 1950, establishing it as a regional focal point of farm and forest learning and free-of-charge public recreational access. George Merck’s project, in turn, led to decades of family and JMF support for efforts to reinvigorate Vermont and New England’s working landscape.

(Courtesy of MFFC)

Serena Merck’s pre-JMF philanthropic work fit the same hands-on, unassuming-yet-impactful pattern—for example, her successful effort in the 1940s to co-found a school for children with developmental disabilities. So did her founding strategy for JMF: to support work on new models of treatment and care for children who, like her son John, had co-occurring neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders.

In broad terms, these and other family initiatives often reflected the spirit of calculated risk-taking George Merck employed at Merck & Co., the U.S. pharmaceutical company he led for decades with an industry-transforming emphasis on breakthrough research.

And George Merck, who died in 1957 at the age of 63, had his own changemaking models. These included Carl Schenck, an elder German cousin who started the first forestry school in the United States, and even the inventor Thomas Edison, a neighbor of the Merck family in the planned community of Llewellyn Park in West Orange, New Jersey.

As a child, George Merck occasionally spent time exploring Edison’s laboratory with two of the inventor’s sons. During one such visit Thomas Edison reportedly told him: “If you just wait for inspiration, and are afraid to experiment, you’ll never learn anything.”

Modus operandi

In its first 18 years, from 1970 to 1988, JMF had no staff and was run entirely by a tightly knit board of five, then seven, family members and advisors assembled by Serena Merck.

The Fund used this hybrid board model of family and nonfamily members throughout its five-plus decades. It did so mainly because friend trustees brought the Fund important experience and perspective, but also because JMF was not expected to be a platform for intergenerational Merck family philanthropic learning and collaboration. George Merck already had established a charitable foundation for that purpose in 1954, three years before his death—the Merck Family Fund, which was thriving under its fourth generation of family leadership when JMF closed its doors definitively in 2022.

(Courtesy of Hatch family)

During JMF’s early years, trustees functioned as a foundation staff, inviting proposals after meeting with organization principals, reading and vetting each proposal, and following up regularly with grantees to assess their performance. Formal board sessions were held every month and sometimes more frequently if the pace and timing of a project warranted.

Low overhead helped the Fund stretch relatively modest assets, but it wasn’t the only way we tried to achieve impact. A willingness to commit these resources—even when economic downturns had eroded the value of our investment portfolio—proved important, too. Unlike many other foundations, we regularly exceeded the minimum 5% of assets that the U.S. Internal Revenue Code requires foundations to give away each year.

Program expansion

An influx of new funds to JMF from the estate of Serena Merck following her death in February 1985 prompted our first significant shift, with trustees identifying several new issue areas for future programming. In discussions on June 16th of that year, board members noted that Serena Merck had made clear in her will that she hoped some of her funds would be used “for a variety of purposes” including, but not limited to, mental health.

Board members agreed that adding JMF programs to address other challenges, including emerging ones, would be consistent with her husband George Merck’s “uncanny ability to detect the real problems of society well before they became generally apparent.” Trustees noted that Serena Merck also “had a broad vision,” concluding that with the Fund’s ongoing developmental disabilities grantmaking established, she would “join her husband in a far broader approach.”

The board then identified a set of “general principles” as criteria for future grantmaking. The first four, in particular, set the tone for our grantmaking over the course of the Fund’s remaining 36 years:

- Our emphasis should be on grants to people rather than grants to institutions.

- The people to whom grants are made should be engaged in programs which we and they wish to promote and which might otherwise not get funding.

- These people should show promise of using the grants in an innovative way.

- We do not wish to adhere to the “safe” or, in other words, the “establishment” course.

The following year, the board agreed to develop programs addressing four new issue areas in addition to developmental disabilities: the environment, nuclear disarmament, international human rights, and global population control.

Charting course

Issue areas were not chosen through a deeply analytical, data-driven process. In some cases, they emerged because one or two trustees believed passionately that the Fund ought to consider grantmaking in a certain field and had already identified potential changemakers to support.

Other trustees would typically lend a hand, using their connections to help assess whether—and, if so, how—JMF funding could make a difference. Such was the case with JMF’s farm and food-systems grantmaking, which began in Vermont in 1986 on the recommendation of board member Judy Buechner, one of Serena and George Merck’s two daughters. The program remained active throughout JMF’s history, evolving along the way to meet emerging challenges and opportunities.

Global human rights grantmaking began soon after, largely owing to the interest of founding JMF board chair Orville Schell, Jr., who co-founded the forerunner group to Human Rights Watch and chaired the rights organization Americas Watch from 1981 until his death in 1987. Inaugurated in honor of Schell after his death, JMF’s human rights program continued for 23 years with active guidance and backing from the beginning from friend trustee Robert Pennoyer.

And grantmaking to promote women’s reproductive rights in the United States came with strong support from trustee Serena Hatch—George and Serena Merck’s elder daughter and Frank Hatch’s wife—while friend trustee Arnold Hiatt inspired a 14-year Fund effort to improve job opportunities in the Northeast.

Systems checks

After new programs were created, trustees regularly reviewed their performance, their impact, and their consistency with the board’s vision for the Fund. This was typically done in two-day retreats that were woven into the regular meeting schedule.

Acting on these reviews, trustees often adjusted program strategies. In an example of one such shift, our population-control program was supplanted by one of its components—the U.S. reproductive rights grantmaking, which became its own freestanding program in 1997. This change of course occurred not only due to the difficulties of achieving impact internationally, but also as a result of moral qualms about focusing funding narrowly on family planning in developing countries riven by other, dire problems such as poor healthcare and malnutrition.

And when warranted, the board did not shy away from eliminating programs entirely. Of the four new grantmaking areas identified in 1986, just one—the environment, which successfully spawned three distinct programs addressing regional farm and food systems, climate and clean energy, and health and environment—remained a focus of activity to the end of JMF’s life.

Our nuclear disarmament program was terminated in 2003 with the recognition that JMF couldn’t have as great an impact in that complex and geographically far-flung field as it might in other grantmaking areas. The program to address job opportunities, created in 1994, was discontinued for similar reasons in 2008 despite having helped to propel the work of a remarkable roster of grantees.

And the next year, we ended our human rights and reproductive rights grantmaking. Our grantees in both issue areas had made impressive contributions. But trustees felt that given the state of those two fields at the time and our relatively limited resources, JMF would find it increasingly difficult to make a major difference in either one in the years ahead. Our board concluded we could achieve greater overall impact by concentrating Fund resources on our four other programs—Climate and Energy, Developmental Disabilities, Farm and Food Systems, and Health and Environment.

Lean and not mean

The Fund could not have created and operated multiple programs—much less monitored their performance and potential—without assembling a staff, a process we initiated in 1988 by hiring Ruth Hennig as grants administrator. Ruth soon became JMF’s first executive director, working in that capacity until 2017 and serving as a member of the board throughout the rest of the Fund’s life.

Two other critical hires—Nancy Stockford, who started at JMF as an associate administrator in 1992, and Christine James, who entered as a program officer 2008—would join Ruth in forming the backbone of JMF’s staff up to and through our spendout.

Nancy and Christine worked in a progression of posts into the Fund’s final year, helping to provide extraordinary continuity and an ever-deepening reservoir of institutional knowledge and expertise. They were assisted by outstanding program officers over the years, including Anna Linakis and Ninya Loeppky.

Consultants were engaged, too, contributing on a part-time basis with proposal analysis and strategic guidance in program areas. Eventually, each program formed a work group that typically comprised a small subset of trustees and a staff member or consultant. These work groups formulated funding and strategy recommendations for the board.

Overall, the operating structure that emerged was still lean compared with those of other foundations. Even at its peak, JMF had just four full-time staff and four paid consultants. Board size over JMF’s history began at five, rose to an average of nine in the 1990s and early 2000s, reached a high of 16 in 2008, then settled at 10 for the duration of the 10-year spendout.

The spare organizational chart enabled a collegial environment of shared decision-making among staff, consultants, and board members, an atmosphere further enhanced by the program work groups, which conducted periodic “deep dives” with the full board.

Reflecting on her experience with JMF after the Fund had closed, Karen Harris, a consultant who helped guide climate and clean energy grantmaking, called that program’s work group “one of the most satisfying and productive aspects” of her work.

“Staff and trustees worked closely together to discuss strategy, explore new approaches, and get to know specific grantees,” said Harris, who following JMF’s spendout went on to become executive director of the Tortuga Charitable Foundation, a funder in the climate and clean energy field. “From those robust and regular discussions, we were able to make better grant decisions and educate the full board about the program as it evolved. I think it is a great model for any foundation that strives to maintain a dynamic grants program that changes with the times.”

Seeking 'sparkplugs'

What JMF sought in grantees, first and foremost, were talented changemakers who, even if they had not yet established themselves, dared to push a bold idea that might help transform their field. Frank Hatch, elected board chair in 1987, liked to call these leaders “sparkplugs.” The term prompted trustees to create a grantee career-achievement prize called the “Sparkplug Award,” climate-unfriendly associations of the name notwithstanding, in his honor when he stepped down in 2006.

Among the 18 winners was Mike Belliveau. While serving as toxics program director at Natural Resources Council of Maine (NRCM), Belliveau offered his vision of a stand-alone state-level organization dedicated to protecting people from harmful chemical exposures. He believed such an organization could build a nimble, highly focused coalition to promote health-protective policies in Maine that would serve as models for other states and, ultimately, for the federal government.

With launch support from JMF, Belliveau and colleague Amanda Sears co-founded the Environmental Health Strategy Center in 2002. Later renamed Defend Our Health, the organization and the statewide health-advocacy network it assembled helped inspire Maine to become a leader in environmental-health action.

Among other achievements, Maine in 2008 enacted the country’s first comprehensive law limiting toxic chemicals in consumer products, and in 2021 it adopted the world’s first ban on non-essential uses of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in all products. Model policies developed by the center and enacted in Maine were successfully exported to other states, creating a substantial ripple effect that spurred federal reform.

“We got a $100,000 startup grant from JMF—that was our only early funding,” Belliveau said in an interview in 2023. “Based on that single grant, Amanda and I built an organization and a diverse, health-based coalition of learning-disabilities advocates and other constituencies. Our goal was to adopt the first state chemicals policy in the nation in five years. It took six years. Now we’re a $2 million organization, with 13 full-time staff positions.”

Belliveau said his organization benefitted not only from the funding, but from ongoing brainstorming with JMF—especially with Ruth Hennig, whose keen interest in environmental-health advocacy had persuaded the Fund to create its health and environment grantmaking area in 1996.

“Ruth and I had a lot of conversations about what’s next in the movement, what the strategy is—a lot of back and forth,” Belliveau said. “There was truly a strategic partnership.”

Agility required

Grantee support did not always occur in a context of linear progress. Often, in fact, it involved helping grantees to move nimbly in the face of sudden challenges, or to rethink their strategies as new possibilities came into view.

The former scenario unfolded after a gunman’s Dec. 30, 1994, attack on two Brookline, Massachusetts, abortion clinics left two employees dead and five wounded.

Within days, our reproductive health and rights program provided funding to the two clinics for counseling assistance and security upgrades. Program funds also were used to assist three grantee partners—the Feminist Majority Foundation, Planned Parenthood Federation of America, and the National Abortion Federation—in planning and implementing a multi-year initiative that markedly improved security for abortion clinics nationwide.

demonstrate in Washington, DC, in 2022.

(Creative Commons/Joe Flood)

Prompt grant support proved helpful for another important reproductive rights initiative: the campaign for U.S. government approval of mifepristone, a drug developed in France to provide women a nonsurgical means of medical abortion.

JMF provided early co-funding for the advocacy effort in 1990, a time when other funders viewed the controversial effort with caution. Led by the Feminist Majority Foundation, the initiative in 2000 won U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of mifepristone, then known as RU-486. The drug, administered in combination with misoprostol, accounted for more than half of U.S. abortions by 2020, becoming a crucial component of women’s reproductive-health services—and a legal target of those pursuing state-by-state abortion curbs.

“Ruth Hennig called me and asked who was helping us,” Eleanor Smeal, president and co-founder of the Feminist Majority Foundation, recalled for this history in 2022. “I said, ‘Nobody,’ because we couldn’t get anyone to help. [JMF was] the first outside funder that sponsored us.”

Supporting introspection

Other grantees felt a need to change direction after questioning their own strategies and concluding that new approaches were required. Community development innovator Rosanne Haggerty, a grantee of our job opportunities program, was a prime example.

When JMF began supporting Haggerty’s work in 1996, the organization she founded, Common Ground, was already widely celebrated for restoring historic buildings in New York City to create mixed-income housing that included permanent and transitional units for the homeless. Common Ground, later renamed Breaking Ground, reopened the refurbished Times Square Hotel at Eighth Avenue and 43rd Street in 1991, and the Prince George Hotel on 27th Street between Madison Avenue and Fifth Avenue in 1999, among many other such projects.

CEO of Community Solutions

Yet Haggerty worried that building housing “wasn’t getting at the fundamental thing: How do we end homelessness?” she recalled in a 2023 interview for this history. “I was feeling validated by the success of our buildings in helping individuals overcome homelessness, but in my heart of hearts knew that what we were doing was only part of the answer. Homelessness was increasing, and it was no one’s job to think beyond individual programs to solve homelessness at the population level.”

JMF grant support to Common Ground, provided from 1996 to 2003, enabled the organization to begin broadening its focus. Funding went to projects ranging from organizational development to the successful piloting of a new housing model for people who found it particularly difficult to get off the street.

But more important, Haggerty said, was the ongoing encouragement she received from JMF board chair Frank Hatch in exploring a more fundamental course correction. Pivotally, she says, he connected her with healthcare-reform leader Don Berwick, founder of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). A partnership ensued, with IHI mentoring Haggerty’s “innovation team” on the use of improvement science in its strategic planning.

Haggerty ultimately created a new organization, Community Solutions, to support and coach communities in building coordinated systems designed to make homelessness rare overall and brief when it occurs. Successively, the nonprofit spawned two paradigm-shifting initiatives.

The first, the 100,000 Homes campaign conducted from 2010 to 2014, helped 186 U.S. communities house a total of 105,580 people whose homelessness was putting them at risk of premature death. The second, called Built for Zero, created an international movement of communities committed to solving homelessness at the population level, for good.

Though these campaigns were not funded by JMF, Haggerty said Frank Hatch’s encouragement and mentorship while chair of the Fund helped set the stage for them.

“At just the right moment, Frank asked, ‘What are you thinking needs to happen next?’ and I was so grateful for the question,” Haggerty said. “It was so important to feel supported while trying to disrupt the conventional approaches to homelessness and redirect our work—which was not making me popular—and for remaining confident that we were onto something. Without that support then, it is unthinkable we would have evolved to the place where we are now.”

Parting of ways

When board chair Frank Hatch resigned for health reasons in 2006 and JMF came under its third generation of leadership, the Fund in many respects had followed the path trustees had envisioned for it following Serena Merck’s death in 1985.

For decades, JMF had been productively engaged in activities of historic interest to Serena and George Merck, namely the quest for improved treatment and care of those with developmental disabilities and efforts to rejuvenate Vermont’s farm economy. But we also were working in other fields of national and international importance ranging from reproductive rights and human rights to climate change and environmental health.

The style of our funding support had followed the intended path, too. Though grants technically were going to nonprofit organizations, they were typically designed to assist specific leaders as they piloted those organizations in their early development or took them in new directions. And our direct board engagement with grantees, despite JMF’s expanded program portfolio and the addition of staff, remained strong and would continue to be so—in many cases focusing on young leaders at the outset of their careers.

“When they first visited our offices on a hot afternoon, the long-legged members of The John Merck Fund board folded themselves into small metal chairs in an 8-by-10-foot office with ceilings that hung so low it nearly grazed the tops of their heads,” Tiffany Bluemle, former executive director of Vermont Works for Women, recalled in 2022. A trade-skills training organization for women and girls, Vermont Works for Women forged a longstanding strategic partnership with JMF. Said Bluemle: “I was a new executive director, grateful for every week that passed without having made a fatal mistake. It marked the beginning of a beautiful relationship.”

At the same time, though, JMF was facing fork-in-the-road questions itself.

For years, there had been discussion about the Fund’s flexible spending policy, under which our annual grantmaking had often exceeded the federally required minimum of 5% of assets. Even though our investment portfolio had preserved its inflation-adjusted value over the decades, there was ongoing debate about whether spending should be strictly restrained to build the Fund’s asset base as high as possible in compliance with the law.

By 2010, the Fund’s emphasis on concentrated program impact had come under discussion, too. Ultimately, these questions prompted trustees representing one of the two family branches with board seats to propose that they resign and set up their own individual family foundations with proceeds from a distribution of half of the Fund’s assets.

Our trustees approved this proposal in September 2010, a decision that left JMF with a portfolio value of $75.9 million and a threshold question for our newly downsized board: perpetuity or spendout?

Change of plan

This question, whether charitable foundations should preserve their assets in perpetuity or spend them out, had become a subject of wide debate in the philanthropic world.

Some contend that long-term preservation of foundation assets hobbles society’s response to pressing challenges, limiting the resources that can be brought to bear in periods of critical need. Others argue that careful maintenance or even growth of a foundation’s real asset levels over time enables the kind of patient, long-term engagement needed to address deeply rooted problems.

Still others reject the idea that one strategy or the other should become a philanthropic standard, insisting that either might be appropriate according to the circumstances of each foundation and the specific issue areas it is addressing.

Despite the various views, our board agreed in short order that JMF’s next step should be a spendout, one that would be carefully planned and conducted over a period of 10 years. The decision stemmed from a shared sense among trustees and staff that given the dire problems facing the country and world—and the strong political forces undermining coherent responses to them—now was not the time to sacrifice impact.

We concluded that at such a juncture, we should preserve or increase—not reduce—our support for initiatives capable of making a genuine difference, particularly with respect to the existential and increasingly urgent problem of climate change.

While the spendout would mean JMF’s disappearance, we felt we should trust that by the end of the 10-year period, new funders would be helping to back the causes we and our existing funding partners favored. And we agreed we should encourage that process by doing as much as possible to help our grantees draw new and varied funders to their fields.

Setting new sights

Our board worked throughout 2011 to determine what shape the spendout should take. Collaborating with an organizational consultant, Mark Leach, trustees concluded early on that given the time limitations imposed by the 10-year spendout, it would make sense to build on existing experience and expertise rather than create entirely new programming. The question was whether to include all, some, or one of our four then-existing program areas.

Ultimately, we decided to focus spendout funding on all four areas—climate and clean energy, developmental disabilities, farm and food systems, and health and environment. The process involved extensive consultations with outside experts to vet individual program strategies, as well as full-board discussions on whether these plans held genuine potential for game-changing impact.

Climate and clean energy, given its overarching urgency, emerged quickly as a top spending priority, as did health and environment grantmaking, in which JMF was now playing a lead role nationally. The developmental disabilities and farm and food issue areas made the cut partly because of their status as “legacy” interests of family trustees, but also because compelling spendout strategies were developed for them.

Three of the four issue areas, in fact, emerged from the spendout-planning process with important strategic adjustments.

In the case of climate and clean energy, JMF would dial down its national-level grantmaking and concentrate almost exclusively on New England. This approach would allow the Fund to help grantees broaden and deepen the remarkable progress they already had made in prodding the region to become an energy-policy exemplar that in some respects rivaled California.

Our developmental disabilities grantmaking would shift from a concentration at the time on basic brain science and would instead focus on translational research and care-modeling projects that more directly target developmental disorders.

Adrianne harvesting at Jordan Farms—home

of the world-famous Chester Gold Corn—in

Chester, Maine.

(Good Shepherd Food Bank, a JMF grantee)

Farm and food grantmaking would move from its largely Vermont-centered support for a wide range of activities to funding a New England-wide food-system strategy aimed at boosting demand by the region’s schools, hospitals, and other institutional purchasers.

Spending and investing

Trustees and staff also drafted a 10-year spending plan for each of the four programs. These plans typically called for relatively low grantmaking levels during the two years immediately following the spendout’s 2012 start, rising to a plateau in the middle years, then declining to zero by 2021.

Importantly, the board authorized work groups to propose adjustments to the rhythm of spending as long as the programs did not exceed their overall 10-year allocation. With this flexibility, programs could more deliberately adapt their grantmaking to emerging challenges and opportunities than might have been the case if, for instance, they had been expected to function under a strict use-it-or-lose-it annual spending regimen.

The Fund’s spendout plans assumed that returns produced by the investment of JMF’s $75.9 million in assets would enable a total of $94 million in spending over the 10-year period. The target, ambitious enough on its own, was arguably made bolder by a simultaneous board effort to rid the Fund’s investment portfolio of holdings that conflicted with JMF’s mission.

Shifting to sustainable investments had been a subject of JMF study, experimentation, and debate for years. Some feared that fully embracing the approach would jeopardize returns and, thus, our grantmaking capacity. But board interest in the concept grew even as we planned the spendout, which ostensibly might narrow the margin for error.

In 2011, a year before JMF’s spendout officially began, trustees approved a sustainable investment program designed to be compatible with the foundation’s new course. Despite some ongoing concern about how the strategy would affect our bottom line, the program that emerged, as JMF Investment Committee chair and friend trustee Anne Stetson put it, “worked for the doubters and the zealots alike.”

It also worked for JMF. Sustainable investments grew from 12% of our holdings in 2011 to a high of 90% in 2018, when we began transitioning the portfolio to liquid assets to guarantee sufficient funds would be available for the final years of the spendout. Over the entire 10-year period of the spendout, investment returns exceeded our target, allowing us to spend a total of $103.5 million—$91.5 million in grants and $12 million in administrative expenses.

“We gained new strength of purpose knowing that our investing decisions were reinforcing our grantmaking decisions,” Ruth Hennig commented after JMF had closed its doors. “Added motivation and clarity came from awareness that our now-finite timeframe gave us just 10 years to achieve impacts. We stayed focused on reaching our program goals while still giving ourselves flexibility to course-correct when needed. It was exciting to take part in such an integrated process.”

Spendout steering

Though our grantmaking approach during the spendout remained remarkably consistent with that of previous years, it necessarily differed in a few respects.

For instance, the Fund’s support for young changemakers and new initiatives, while still evident in numerous grants, came amid more extensive collaboration with seasoned leaders and organizations, some of whose relationships with JMF dated back to their formative years. This shift reflected a need to lever as much existing capacity as possible in order to meet the goals spelled out in our homestretch strategies.

Another difference stemmed from the simple fact that the Fund now had a sunset date. The deadline prompted us to place greater emphasis on capacity-building support, recruitment of co-funders, and grantee collaboration to help advocacy partners not only accomplish their immediate goals, but also strengthen themselves individually and collectively for the future.

Peter Allison, executive director of Farm to Institution New England (FINE), helped foster such collaboration in the farm and food program with Christine James, who served as a JMF program officer before becoming our executive director in 2017.

FINE was launched with JMF support in 2011 to connect New England farms and food producers to the region’s institutional buyers through cross-state collaboration and infrastructure development. As Allison recalled in a 2022 interview for this history, James took pains to ensure that where appropriate, grantees conferred with FINE and amongst themselves on how they might cooperate on the projects they pitched.

“JMF insisted we work together across the food system regionally, and this increased our overall connectedness and resiliency,” Allison said. “I used to joke that when JMF board dockets came out, my phone would light up with calls [from organizations that had made JMF funding requests], and I’d ask, ‘Did Christine tell you to call me?’”

The spendout also saw JMF begin to address racial equity, albeit indirectly through support for initiatives such as Migrant Justice’s Milk with Dignity campaign, which sought improved wages and working conditions for New England’s immigrant dairy workers. We also backed GreenRoots, a group combating pollution in the predominantly minority communities of Chelsea and East Boston, Massachusetts, and West Harlem Environmental Action, for campaigns to remove toxins from consumer products used by women and girls of color.

(GreenRoots)

Still, we clearly should have paid attention to race and ethnicity in our program analysis and planning far earlier and far more systematically, a realization underscored amid the national introspection that followed the murder of George Floyd in May 2020.

For funders, efforts to find more proactive equity approaches meant rethinking not only the destination of grants, but also the degree to which those funds are conditioned.

Although at the end of its life, JMF gained some experience on the latter score as well. Specifically, we joined the Henry P. Kendall Foundation in steering $650,000 in food-system support to the New England Grassroots Environment Fund, where distribution of the funds would be overseen by a cohort of racially, ethnically, and economically diverse community stakeholders.

“The board remained open and responsive to the needs and requests of grantee partners right up to the very end,” said Christine James in 2023. “Those partners by then included grassroots groups whose perspectives and strategies were informed more by their lived experience in communities most affected by environmental harm than by academic study or policy advocacy. The willingness to listen to new voices and to adapt the foundation’s approach in response is one of the most important contributions to the practice of philanthropy that The John Merck Fund leaves behind.”

Lights out

JMF ceased to exist on Dec. 31, 2022, following an organizational wind-down overseen, fittingly, by Nancy Stockford, who had supervised JMF administrative and financial functions over the decades with remarkable efficiency and grace.

The wind-down prompted staff and trustees to reflect on the Fund’s half-century collaboration with our grantee partners. The fruits of that collaboration are chronicled in the individual program histories now available on this website. To name a few, all of them from the 10-year spendout:

- Climate and clean energy advocates leveraged greenhouse-gas emissions-reduction mandates they had successfully advanced in all New England states but New Hampshire, driving regional action ranging from residential and business energy-efficiency improvement to the approval of offshore wind-power projects.

- Scientists opened new pathways for research, treatment, and care targeting Fragile X, the most common known cause of inherited intellectual disability, and piloted improvements in standard newborn screening to provide early detection of inherited developmental disorders.

- Ongoing development and rejuvenation of New England’s food system allowed the region’s farmers and food producers to help keep communities nourished as COVID-19 lockdowns paralyzed the world’s vertically integrated food supply chain.

- Campaigns to reduce the presence of toxic chemicals in consumer products spurred corporate and state policy action, as well as a rewrite of the federal Toxic Substances Control Act.

These and many earlier achievements were highlighted in a spendout-ending Zoom celebration that JMF held on the evening of Oct. 14, 2022, for current and former grantees, staff, and board members. Also recognized was the remarkable cooperation built through the years between JMF and its grantee partners, a collaboration in many ways more rewarding than any proposal approved or milestone reached.

RTI researcher Don Bailey recalled that early in the spendout, a simple comment made to him during a discussion with JMF’s developmental disabilities work group inspired him to broaden his plans for a statewide newborn-screening project in North Carolina.

“[The comment] was something like, ‘You know, you might want to think a little bigger,’” said Bailey, an expert on young children with developmental disabilities. “That simple but powerful statement has served as something I’ll never forget. It has served as a North Star for me and my team.”

For JMF trustees and staff, the dedication, skill, and creativity displayed by grantees such as Don Bailey served as a North Star, too, illuminating avenues of progress amid societal problems that might otherwise have seemed intractable. Although the Fund closed its doors, new and different cooperation between former “JMFers” and grantee partners seemed likely in the future.

“The opportunity to engage in and contribute to all these efforts was, for me and my siblings, a great privilege,” Whitney Hatch, JMF’s chair during the final three years of the spendout, said in 2023. “We were able to work closely with our parents’ generation, dedicated friends, JMF’s phenomenal staff, and the terrific line-up of organizations and leaders we had the good fortune to know. The good news is that this privilege didn’t end on Dec. 31, 2022, when JMF closed its doors. Indeed, we look forward to tracking the growth and success of our past grantees and to the opportunity to pick up the phone and continue to collaborate with them and with our fellow trustees and staff. How great is that?!”