Farm and Food Grantmaking

Table of Contents

(Vermont Land Trust)

If our farm and food grantmaking had a touchstone, it was southwestern Vermont’s Mettowee Valley, where bucolic riverside farmsteads unfold along state Route 30 from Dorset in the south to Wells in the north, bracketed by wooded peaks.

Beginning in the Mettowee Valley in 1986 and extending throughout New England over more than 35 years, we joined grantee partners to address myriad challenges in pursuit of an admittedly outsized goal: to reinvigorate the region’s working landscape and agricultural economy.

This meant conserving farmland and keeping it affordable for next-generation farmers—a daunting task, given changes in land use in many parts of New England owing to sprawl and demand for vacation property, and related increases in land prices.

It involved fostering alternatives to a conventional dairy-farming model undercut for decades by an influx of cheaper milk from larger-scale Midwestern and Western producers. It also meant attempting to build institutional demand for New England–produced food, boosting the reliability of supply chains needed to meet that demand, and attracting active state and federal government support for these efforts.

More broadly, there was a long-ignored need to address equity issues such as access to fresh food for low-income residents, improved working conditions for farmworkers and food supply-chain workers, and capital availability for food entrepreneurs too often excluded from financing opportunities.

Hurdles on all these fronts remained when we delivered our last grant in 2021. Indeed, some of the challenges had become steeper after the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, and would be exacerbated in 2022 amid economic fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

But as the pandemic revealed, important progress had been made, too. During the COVID lockdowns, local suppliers and partners in many communities stepped in to keep food available despite the failure of the national agribusiness supply chain. In doing so, they demonstrated the power of work done over decades to strengthen and diversify New England’s food system.

Among the many large and small contributors to the region’s efforts to develop its food system over the years were JMF grantees, including:

- Farm to Institution New England (FINE), which engaged with stakeholders ranging from farmers to food hubs to college dining directors to help boost regional food demand and supply;

- The nonprofit Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund, which launched a state government–supported process for food system planning and development that spurred similar initiatives in other states;

- The Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association, which promoted diversified food production in Aroostook County, Maine—by far New England’s biggest storehouse of agricultural acreage;

- Red Tomato, a food distribution enterprise that connected growers and institutional and wholesale customers throughout the Northeast;

- CommonWealth Kitchen, a nonprofit business incubator in inner-city Boston that provided a launchpad for food entrepreneurs making and marketing everything from vegan cupcakes to Jamaican jerk spices; and

- The farmworker advocacy group Migrant Justice, which developed dairy labor standards and—through its Milk with Dignity program—persuaded Ben & Jerry’s ice cream company to require the adoption of these labor standards by its milk suppliers.

(hornickrivlin.com)

By the end of our spendout, grantee partners helping to lead these and countless other efforts felt confident that New England, despite ongoing challenges, had laid critical groundwork for the future of its regional food system.

“The movement is a lot stronger now,” Peter Allison, the executive director of FINE, said in 2022. “It’s true that farmland is still being lost, and it’s still hard to be a farmer, but a lot of great food is being produced in our region, and people in New England are strongly identifying with it. A dynamic network has developed to make this happen for reasons including equity and food access, better nutrition, and water and climate protection. It’s exciting to be part of, and I’m optimistic. This movement isn’t going away.”

Vermont Land Trust

JMF Grants 1986-2021: Farm and Food

Total $ Amount

$37,365,388

Years of Program

1986-2021

# of Grants

748

Family roots

JMF’s farm and food grantmaking grew out of the love that our founder, Serena Merck, and her husband, George Merck, shared for Vermont. Beginning in the early 1940s, the couple and their three children made summer migrations to the southwestern Vermont town of Rupert, part of which lies in the Mettowee Valley. There, George Merck found an outlet for his interest in forestry and demonstration farming.

Ever involved in projects, even when ostensibly on vacation, he bought a large swath of Taconic Range acreage within the town’s boundaries, and in 1952 he established what came to be called the Vermont Forest and Farmland Center. The center was granted nonprofit status and named the Merck Forest and Farmland Center after George’s death in 1957. Encompassing 3,500 acres today, the striking property of upland forest and fields with panoramic views west to the Adirondacks provides outdoor educational programming as well as backcountry recreational access to the public year-round, free of charge.

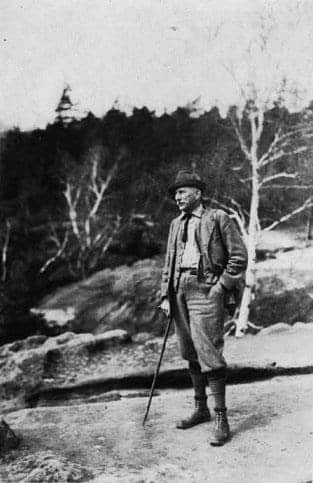

George Merck owed his fascination with natural and working landscapes in part to Carl Schenck, an elder cousin from Germany who was hired in 1895 as forester for George Vanderbilt’s vast Biltmore Estate near Asheville, North Carolina.

(Special Collections Research Center at NC State University Libraries)

George Merck liked to refer to himself as a “synthetic nephew” of the quarter-century-older Schenck, who founded the Biltmore School of Forestry in 1898, the first forestry school in the United States. At Biltmore, Schenck provided an immersive program in scientific woodland management for scores of trainees—among them George, who interned at the school as a teen and was made an honorary graduate in 1950.

Many other members of the Merck family developed a strong interest in natural and working lands, including Serena Merck and the couple’s daughters, Judy Buechner and Bambi Hatch, both of whom served on the JMF board. With both daughters’ encouragement, Vermont farmland preservation became one of several new grantmaking areas that were created after JMF received a significant influx of new funds from Serena Merck’s estate following her death in 1985.

This grantmaking, begun in 1986, supported projects at Merck Forest and Farmland Center for a number of years. But the vast bulk of the funding—$25 million over the 25-year period—went elsewhere, starting with farmland conservation in and around the Mettowee Valley, then to varied farm and food initiatives in Vermont, and eventually across New England.

‘Necessary evil’

Our Mettowee Valley grantmaking began taking shape after a 1986 meeting that JMF’s board held with the Ottauquechee Regional Land Trust, a land conservation organization that would soon be renamed the Vermont Land Trust (VLT). The discussion centered on what might be done to help keep the Mettowee Valley and its rich bottomlands in agricultural production, a question that Judy Buechner, a Vermont resident, had raised with the trust a year earlier.

(Blake Gardner)

What emerged was an initiative in which local farmers were invited to put conservation easements on their properties in return for compensation. In doing so, participating farmers effectively accepted limitations on their rights to develop their land. But in the process, they gained capital they could use to maintain or improve their farms, or to facilitate the property’s transfer to next-generation family members. They also could rest assured that the land would not be subdivided if eventually sold, effectively boosting its chances of remaining in agriculture.

The initiative came at a critical time. Rural New England generally and Vermont in particular were gaining new seasonal and year-round residents at a torrid clip as city and suburban dwellers embraced country living. The trend was very much felt south of the Mettowee Valley in the communities of Dorset and, south of that, Manchester, with land values rising as a result.

North of Dorset, however, farm families—for the time being, at least—were staying put.

“The first time I drove [north] up Route 30 from Dorset, in 1985, I wondered how it was possible that, given its close proximity to Dorset, Manchester, and New York State, the [Mettowee] Valley had seen virtually no subdivision and development,” former VLT President Darby Bradley wrote in a 2022 essay. “The answer was that none of the farm families there had been willing to sell off parts of their land. But that seemed likely to change. The existing owners were getting old, and high land values made it impossible for new farmers to buy farms.”

(Vermont Land Trust)

Yet new resources for farmland conservation were becoming available, too, most importantly under the aegis of the Vermont Housing and Conservation Board (VHCB). This innovative state agency was established in 1987 to simultaneously support land conservation and the construction of affordable housing using funds from sources including the state real estate transfer tax.

Vermont Land Trust and The John Merck Fund proposed to VHCB that if it would cover half the cost of farmland conservation in the Mettowee Valley, they would provide the remaining 50% through JMF grants and VLT fundraising. The agency responded that it could not make funding commitments until concrete Mettowee Valley conservation proposals were presented. But it promised to give these careful consideration—and made good on its pledge. Co-funding of VLT-initiated projects by VHCB, and eventually by the federal government as well, would become a mainstay means of conservation in the Mettowee Valley and elsewhere in Vermont, establishing the state as a national model in farmland protection.

In 1988, JMF helped seed this work by pledging up to $3 million for the establishment of a revolving fund whose goal was to assist the VLT in preserving Mettowee Valley farmland, attracting government co-funding where possible.

“Land conservation up to then involved people with resources who could donate a conservation easement on their property,” Gustave “Gus” Seelig, a co-founder of VHCB and its longtime executive director, recalled in 2022. “The availability of public funding helped make [farmland conservation] possible for working farmers. In securing it we had promised the Legislature we would be able to leverage other money from private sources. So when VLT and The John Merck Fund provided support early on, it was key, because it legitimized what we were doing. It helped us expand the program.”

Particularly in the early years, however, there was no guarantee that farmers would want to place conservation easements on their property. Few relished what that process entailed—agreeing to land-development restrictions overseen by the Vermont Land Trust.

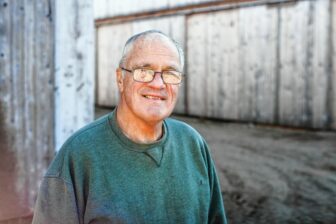

(Caleb Kenna)

The incentive, on the other hand, was the promise of funds that could help farmers keep their land in agriculture in the face of mounting economic pressures. To engage farmers, community officials, and others on an ongoing basis, VLT went local. It established the Mettowee Valley Conservation Project, which included a local office and director—the first of which was Jacki Lappen—as well as town advisory bodies and a valley-wide steering committee of Mettowee Valley stakeholders.

“I remember that at one Mettowee conservation meeting, a farmer named Fred Stone stood up and said, ‘You know, the Vermont Land Trust is a necessary evil,’” Donald Campbell, who led VLT’s work in southwestern Vermont, recalled in 2022. “That tells it all from the farmers’ perspective, which is: ‘I wish we didn’t have to do this, because you’re going to have the land trust lording it over you. But in the absence of the land trust, we’re going to become Manchester.’”

Confidence and collaboration

Evoking mixed emotions like these, farmland conservation in the Mettowee Valley and elsewhere in Vermont required patience. Progress initially was slow. But once the first three Mettowee Valley families conserved their farms in 1989 and 1990, Bradley remembers, other farmers became more receptive as they began viewing VLT as a committed partner in preserving the region’s agricultural character.

(Vermont Land Trust)

In the ensuing years, 10 of the 11 largest dairy farms along the Mettowee River came under conservation easements, along with numerous other farm and forest tracts in the region, creating a notable example of large-landscape conservation.

By 2022, VLT had extended its efforts to all corners of the state, brokering the conservation of more than 620,000 acres of farmland and forest in the 45 years after its founding.

For many participating farmers, the easements represented a way not only to address economic challenges, but, more broadly, to do their part to help keep the working landscape intact.

“I watched my parents do a really good job running a dairy business while raising a family, but it is increasingly clear it has to keep evolving to be a sustainable family farm,” said Seth Leach, son of Tim and Dot Leach, who in 1997 conserved Woodlawn Farm, which is located in the Mettowee Valley. “This valley is such a special place, worth protecting, and we are happy to share it with the world.”

Grantmaking for this work was not limited to co-funding conservation easements. JMF and a subsequent VLT funding partner, the Freeman Foundation, supported the land trust in boosting its operating capacity. In JMF’s case, this capacity-building help took the form of a three-year grant in the late 1980s that allowed VLT to hire its first vice president of operations.

“The money which JMF invested in the three-year grant could have been used to protect one more working farm,” Bradley wrote in 2022. “Instead, it enabled VLT to move to a higher level of professionalism. That, in turn, put VLT in a position to protect hundreds of more farms when the pace of land conservation accelerated in Vermont, after Howard Dean became governor in 1991 and the Freeman Foundation arrived [as a VLT funding partner] in 1993. Coming at a critical time in VLT’s evolution, JMF’s investment proved to be transformational.”

Major challenges nevertheless loomed along the way. For instance, a growing number of city dwellers paid top dollar for conserved farms that they then used as year-round or seasonal estates. Because of the conservation restrictions, the land could not be subdivided, but it fell out of full-time agriculture, undercutting the objective of preserving Vermont’s working landscape.

Recalling the first such sale in the Mettowee Valley, Campbell said: “That gave us a wake-up call. We realized we might be converting working farms into gentlemen’s farms. Everyone wanted a piece of Vermont, and there was enough money in New York and Boston that conserving farms could be creating potential estates.”

This worry prompted VLT to negotiate agreements with existing and new easement holders stipulating that conserved acreage being sold must first be offered to the easement holder—in this case, VLT—at a lower price based on its agricultural value. That would give VLT a chance to structure a lower-priced transaction aimed at allowing a new farmer to take over the property and keep the land in agriculture. These “option to purchase at agricultural value” provisions, known as OPAVs, became a standard part of future farmland conservation easements.

Still more difficult was ensuring that conserved farms, even if successfully conveyed to next-generation farmers, would survive economically, given that so many of them depended on the ever-precarious conventional dairy industry. After focusing almost exclusively on farmland conservation initially, our farm and food grantmaking increasingly targeted this “farm viability” challenge.

Building the bottom line

Beginning in the mid-1990s and continuing until the start of our spendout in 2012, we collaborated with grantees and other funders on an expanding spectrum of initiatives to boost economic opportunity for farmers and food producers, almost exclusively in Vermont.

In part, this work involved promoting supplemental and alternative agricultural activities such as sheep, lamb, goat, and grass-fed beef operations; cheese and yogurt production; cultivation in wood-heated greenhouses; and even on-farm agriculture tourism.

It also included the promotion of agricultural practices that could benefit the environment while also contributing to the bottom line—among them, composting of agricultural waste, rotational grazing of livestock, and conversion of traditional dairies to organic operations.

With guidance from our program consultant at the time, Jamie Cherington, we partnered with numerous organizations in this work. These groups included the Northeast Organic Farming Association of Vermont (NOFA-Vermont); the American Farmland Trust; the VLT; the Highfields Center for Composting; Shelburne Farms estate and educational center; and the Intervale Center, a nonprofit that promotes farm viability and land sustainability.

We also supported initiatives to establish business planning and financial support for agricultural entrepreneurs. For instance, JMF helped lay the groundwork that led to the launch in 2003 of Vermont’s state Farm and Forest Viability Program, a division of the Vermont Housing and Conservation Board that at the time of our spendout was managed by Liz Gleason.

The program was modeled in part on an existing program in Massachusetts with guidance from a former agriculture commissioner of that state, Jay Healy, whom JMF board chair at the time, Frank Hatch, introduced to Vermont officials and farmland conservationists. The Farm and Forest Viability Program connects small farm, food, and forest enterprises—typically more than 100 in a given year—with consulting expertise drawn from institutions and groups including the University of Vermont, the Intervale Center, and NOFA-Vermont.

And when funding permits, the program gives farmers and food entrepreneurs grant support for activities including developing food hubs, transitioning traditional cow dairies to organic production, and establishing supplemental on-farm enterprises. The activities of these enterprises have ranged from cheese- and sausage-making to agritourism, composting, and the production of farm-based hard cider and spirits.

“We were ahead of the game in creating a strong continuum of business and technical assistance here in Vermont capable of assisting a wide range of agricultural enterprises and services,” said Ela Chapin, who led Vermont’s farm-viability program from its inception in 2006 to 2021. Chapin, who in 2022 won a seat in the Vermont House of Representatives, added, “For instance, I don’t believe we would have seen the same success in Vermont’s on-farm cheesemaking boom if we hadn’t already been investing in that continuum.”

JMF also assisted in launching the Flexible Capital Fund, which provides creative financing in the form of near-equity capital for growth-stage Vermont companies active in the areas of sustainable agriculture and food systems, forest products, and clean technology. As the only licensed lender in Vermont to provide royalty financing, or revenue-sharing capital, the Flexible Capital Fund invests in Vermont companies that help complete or strengthen their respective supply chains.

An initiative of the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund (VSJF), a nonprofit entity created by the Vermont Legislature, the Flexible Capital Fund was created to speed development of Vermont’s sustainable food system, though it has helped nonagricultural sustainable businesses as well. The fund has assisted a wide variety of Vermont-based farm and food businesses such as makers of specialty cider, gluten-free cookies, kombucha, and smoked meats. In some cases its financing has allowed such companies to reach the scale needed to tap the national market.

Further seed support from JMF and other funders helped enable VSJF in 2011 to begin offering more sophisticated business management coaching to a limited number of mid-scale enterprises poised for major growth. By the end of our spendout in 2021, the number of executive-level entrepreneurial coaches in the program had reached nine, and more than 60 businesses had received guidance, using it to improve operations, pay better wages, and access new markets.

Taken together, these services not only encouraged the emergence of alternatives to dairy in the state’s agricultural economy, but they also helped farmers and food producers respond to demand for a greater variety of alternative products within the dairy sector itself—yogurt and cheese, for instance.

This transition was crucial, according to Ellen Kahler, VSJF’s longtime executive director. Diversified, value-added, and organic dairy producers and processors expanded market opportunities as more small- and mid-scale conventional dairy operations folded due to market forces beyond their control, she noted in an interview in 2022. Yet at the same time, Kahler added, large-scale conventional dairy operations remained viable.

“Look at organic dairy, and at value-added dairy that is producing things like artisan cheese,” she said. “While consumers may be drinking less fluid milk than a few decades ago, they are actually consuming more dairy products overall. There has been quite an expansion in the marketplace. The consumer [has changed], and thus production trends have changed.”

Links in the chain

Improving food system infrastructure became an objective as well, with initiatives including the development of distribution channels connecting communities with farmers markets, hospitals with suppliers of locally grown food, and chefs in Vermont, Massachusetts, and New York with Vermont cheese and beef producers.

An early grantee in this work was Vermont Fresh Network, an alliance of farmers, chefs, and consumers committed to expanding the market for the region’s sustainably grown food. Professional colloquia that the network organized in 2008–2009 gave a sense of the range of stakeholder engagement the Vermont Fresh Network and other grantees helped create.

At one event, “Chef Talk,” chefs explored new ways to use local foods in their kitchens and how to maintain successful relationships with local farmers. At another, “Where’s the Beef?”, farmers, processors, food service managers, and distributors discussed how to clear bottlenecks in the state’s beef industry.

And at a third event, “Distribution Meet and Match,” food distributors were stationed at tables where farmers and food producers could approach them and describe their products. Said a Vermont Fresh Network report on this “speed-dating” event: “Producers and distributors had the opportunity to investigate who’s who, where the trucks are, and how farmers get their products on those trucks.”

at Shelburne Farms.

(Sarah Bell)

Infrastructure development also extended to academia. JMF helped provide seed funding for the establishment in 2004 of the Institute for Artisan Cheese at the University of Vermont. A pioneering educational and research center, the institute fostered safe, high-quality craft cheesemaking in the state and trained more than 1,200 individuals from 46 states and seven countries. (The institute dissolved in 2013 amid declines in federal and private funding support, but not before contributing considerable training and expertise to artisanal cheesemakers in Vermont and beyond.)

Our grantee partners also addressed the demand side. We helped them do so by funding promotional support for maple syrup marketing, know-your-farmer campaigns, and tourism initiatives such as the Vermont Cheese Trail and the Vermont Cheesemakers Festival at Shelburne Farms, in Shelburne, Vermont.

Systems thinking

Projects such as these reflected a growing sense that by strengthening linkages between farmers, food producers, distributors, consumers, and, eventually, institutions, Vermont-grown food could gain recognition and weight in the regional economy.

a local organic vegetable, flower, and

medicinal herb farm.

(NOFA Vermont)

That view underpinned a 2009 grant that in many ways set the stage for our farm and food strategy during the spendout: seed support for a first-ever strategic plan to guide state investments in Vermont sustainable agriculture and food systems.

Work on the plan, called Farm to Plate, was carried out by the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund under the authorization of the state Legislature and the leadership of Ellen Kahler. Involving broad stakeholder engagement before its release in January 2011, the plan spotlighted key food system choke points and gaps, and made priority recommendations on how to address these problems over the coming 10 years.

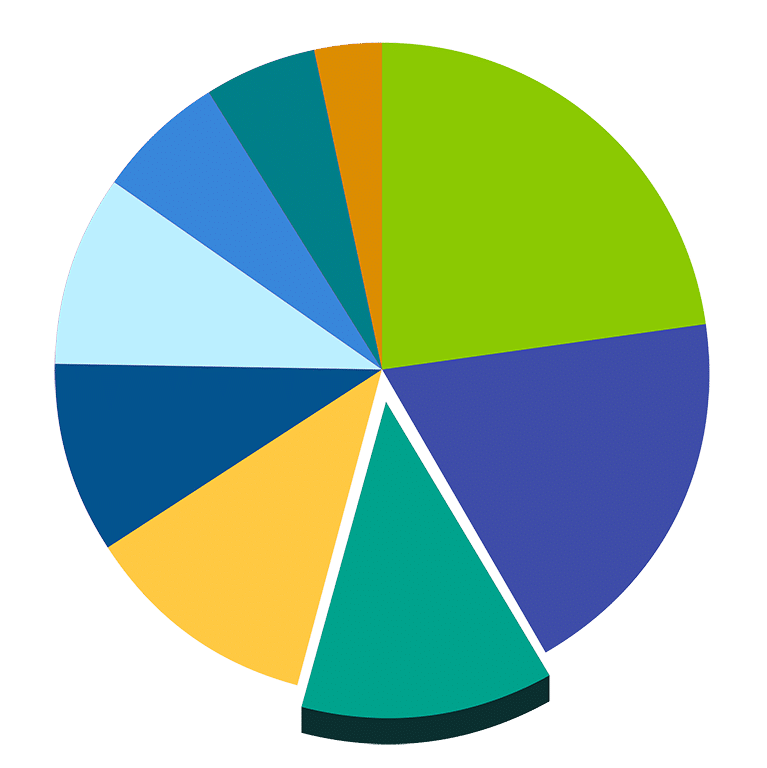

The state of Vermont invested $100,000 a year to advance the initial 10-year Farm to Plate food system plan, and the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund lined up additional support from JMF and other philanthropic funders. During the plan’s first decade, the economic output of Vermont’s food system grew by 48%, from $7.5 billion to $11.3 billion. Of this $11.3 billion, $3 billion, or 26.5%, came from food manufacturing, Vermont’s second-largest manufacturing sector.

Over the same period, Vermont’s food system added 6,560 net jobs, an 11.3% increase, and local food purchases grew from $114 million to $310 million, or 5% to 13% of overall food spending in the state.

The plan’s role in encouraging that growth would prompt state lawmakers in 2019 to authorize the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund to draft a follow-on 10-year strategic plan. That next-stage blueprint was released in February 2021 under the leadership of Jake Claro, manager of the Farm to Plate Network.

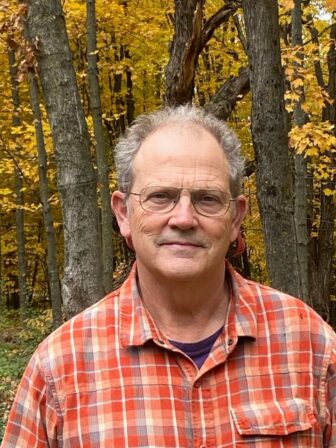

Chuck Ross, who served as Vermont’s secretary of agriculture from 2011 to 2017, said the Farm to Plate planning process encouraged the important, even if still-emerging trend toward diversification in Vermont agriculture.

“During my tenure [conventional] dairy farms in Vermont, which had been the 800-pound gorilla for decades, were declining in numbers,” Ross recalled in 2022. “But because of the farm-to-plate movement and the appeal of new, diversified agricultural products, we saw an increasing awareness of the importance of agriculture for communities.”

Going regional

When we launched JMF’s 10-year spendout in 2012, we had narrowed our grantmaking to four issue areas. Farm and food work was among them, but with two main twists.

The first was geographical: we widened our focus to New England rather than concentrating nearly exclusively on Vermont. This expansion, we hoped, would allow us to boost our impact and encourage a holistic approach, where possible, to the development of New England’s food system.

The second course correction was to make a special effort to develop institutional demand for local and regional food. Underlying that shift was the realization that organic and “buy local” campaigns had been so successful that the flow of goods from small- and medium-sized producers to direct sales venues such as farmers markets and community-supported agriculture outlets had approached saturation levels.

Expert advisors including Jay Healy and Kathy Ruhf, longtime coordinator of the Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Working Group (NESAWG), argued that the region’s food system needed to tap steadier, larger-scale demand in order to grow. By that they meant contract purchases by institutions such as hospitals, colleges and universities, K-12 schools, assisted-living and long-term care centers, prisons, and military bases, as well as local and state government entities.

Collectively, entities like these were spending hundreds of millions of dollars a year to feed tens of thousands of people a day. And compared with other large buyers such as supermarket and restaurant chains, institutions might be more likely to weigh factors other than profit when making procurement decisions. Supporting local suppliers of sustainably grown food, for instance, might help them burnish their image as “good neighbors” concerned about their host communities.

Because building institutional demand would require enormous collective effort, we knew we would need to promote far greater collaboration than we had in the past with and among grantees, funders, government, and other stakeholders. Fortunately, others working to build New England’s food system shared that view, including regional funders JMF was cooperating with in venues such as the Vermont Food Funder network.

Among them was Gaye Symington, a longtime JMF collaborator who headed the High Meadows Fund, a Vermont philanthropy based at the Vermont Community Foundation (VCF). High Meadows supported community-building and environmental protection for 16 years before transferring its remaining assets to VCF in 2021.

“What we realized is that it’s not only about a balance sheet of positives and negatives,” Symington, a former speaker of the Vermont House of Representatives, said in 2022. “It’s also about what relationships you are building and where those can take you.”

Testing, testing …

From the first grantmaking dockets of our spendout, we put our hypothesis to the test, investing in initiatives designed to grow institutional demand for New England-produced food across the six-state region. The initiatives we supported included:

- The nonprofit campaigns Health Care Without Harm and Real Food Challenge, which worked to promote purchases of sustainably produced regional food by New England hospitals and institutions of higher learning, respectively;

- Farm to Institution New England, a regionwide stakeholder network that JMF helped seed to boost the use of regional food not only in hospitals, colleges, and universities, but also in K-12 schools, prisons, and other facilities;

- Growers associations, including the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association, the Vermont arm of New England Northeast Organic Farming Association, to increase supply;

- Nonprofit food hubs and processing centers to help aggregate and distribute regional food—among them Food Connects, the Intervale Center, Red Tomato, the Western Massachusetts Food Processing Center, Food Works at Two Rivers Center, and the Center for an Agricultural Economy; and

- Collaborative work by several of these groups to decipher and influence institutions’ notoriously opaque procurement practices and food service contract terms.

As this work progressed, we came to recognize that the “simple” solution of securing bigger customers for New England producers would be anything but.

(University of Massachusetts)

For starters, food service management companies and broadline distributors staked their profitability on ready access to the consistent, high-volume, year-round production that favors California’s mega-farms over New England’s smaller producers. In addition, these food service companies had little interest in altering the status quo. Too often, food-purchasing institutions shared that lack of interest. Colleges, universities, and hospitals ostensibly concerned about the economic, social, and environmental health of their communities, continued to focus overwhelmingly on cost cutting and convenience in their procurement decisions.

There were encouraging exceptions, among them educational institutions including UMass-Amherst and the University of Vermont; healthcare providers such as UVM Medical Center in Burlington, Vermont, and Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts; and the Portland, Maine, public school system.

However, it became clear that without a coordinated call for change from outside institutions’ walls, the effort to gain New England producers even a modest portion of the institutional food-procurement millions would be Sisyphean. More had to be done to alert the public to the economic, social, and environmental benefits that New England’s farmers and food producers bring—and to the costs of continued deterioration of New England’s agricultural economy.

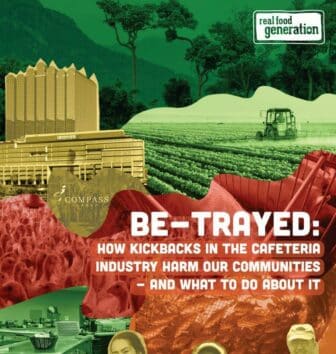

Our grantee partners responded. For example, Real Food Generation, the advocacy group behind the Real Food Challenge campaign, exerted pressure on institutions of higher education to buy from regional farmers and food producers whose practices align with the organization’s recommended food-sourcing standards.

(Uprooted & Rising)

Initially, this form of advocacy succeeded, with more institutions shifting a portion of their food purchasing to smaller regional suppliers operating under more sustainable standards, but the early adoption soon slowed. So Real Food Generation tried another tactic. It painstakingly investigated the murky world of food service company contracts, and the difficulty of untethering campus dining services from them, producing a report titled Be-Trayed: How Kickbacks in the Cafeteria Industry Harm Our Communities – And What to Do About It – North American Marine Alliance (namanet.org).

Armed with a more sophisticated understanding of the forces at work in the institutional food supply chain, Real Food Generation helped organize initiatives such as the Real Meals Campaign, Uprooted & Rising, and the Community Coalition for Real Meals. These efforts tapped the power of students but also of farmers, anglers, ranchers, food workers, environmental advocates, and global justice activists to push for change in the food industry.

Technical assistance

Our original theory regarding changing food procurement needed adjusting in another respect. We had assumed the region’s farmers and food producers would readily enter the institutional market once hospitals, colleges, K-12 schools, and other institutions signaled a willingness to buy from them. But small-scale food growers and suppliers had a far harder time than we expected ramping up to meet the product-volume and supply-consistency requirements of even relatively small institutional customers.

In fact, many producers knew little about the workings of institutional supply chains, making it hard for them to enter that market on their own. And more fundamentally, few knew how to go about determining whether serving an institutional customer would be beneficial for them in the first place.

(Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association)

It was clear that technical assistance had to become more readily available to suppliers interested in testing the institutional waters, and a range of new and past grantees moved impressively to meet the need. These grantees included the Vermont Housing and Conservation Board’s (VHCB’s) Farm and Forest Viability Program, the , NOFA-Vermont, the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association, the Maine Farmland Trust, Land for Good, and the New Hampshire Community Loan Fund. With JMF grant funding, these entities offered expanded support, largely free of charge, to farmers, seafood harvesters, and food entrepreneurs looking to grow their businesses and tap institutional markets.

Demand for this assistance soon exceeded the capacity of the organizations providing it. To help meet this demand we contributed to the founding of the Agriculture Viability Alliance, a network dedicated to building public and private support for providers of technical assistance serving farm and food businesses.

The alliance, created in 2017, grew out of biannual conferences that JMF and partner funders co-sponsored for farm-viability advocates nationwide. Its charge was to respond to the business-development needs of farmers and food entrepreneurs not only in New England, but also in an adjacent “food shed” with close ties to the region—New York’s Hudson River Valley. By the end of JMF’s spendout period, the Agriculture Viability Alliance had hired its first staff, created a steering committee, and established two working groups, one on workforce and professional development and the other on resource and policy development.

The Farm to Institution New England (FINE) network, meanwhile, helped regional food producers find entry points into New England’s institutional market. An illustrative example is that of Doug Feeney, a Cape Cod fisherman. Feeney and other members of his fishing co-op were frustrated that the bulk of their catch—small bottom-dwelling sharks regrettably named “dogfish” (Squalus acanthias)—typically wound up being exported for lack of local demand. Feeney wanted to see his co-op’s catch help feed his neighbors.

Though he had managed to interest a few local chefs in the species, he needed steadier, higher-volume demand of the type that might be found in New England colleges, universities, hospitals, and correctional facilities.

But how to tap it?

Forgoing precious fishing time, Feeney attended the 2017 FINE Summit, an annual convening of stakeholders in the regional food movement. There, he shared his story with 500 attendees—one of whom, a representative of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), followed up with him soon after.

Nine months later, Feeney’s co-op had won $500,000 from the USDA to improve and rebrand its product as “shark bites,” dramatically expanding sales of the small sharks they catch to institutions. The process included a fair-price contract that guaranteed fishing co-op members a better livelihood.

Food system planning

Our new regionwide strategy also sought to encourage replication of Vermont’s Farm to Plate initiative by promoting food system planning in other New England states.

To that end, we supported the nonprofit advocacy group Food Solutions New England (FSNE) in the drafting of an influential document titled A New England Food Vision, which was issued in 2014. Drawing on three years of collaborative research and stakeholder engagement, the document made recommendations that culminated in a “50-by-60” goal for the region to produce half its food by 2060. Though presented as a vision rather than a plan, FSNE’s report nevertheless spawned concerted food system planning efforts at the state, municipal, and regional levels.

Grantee partners also spurred food system planning initiatives in individual states, including the Maine Food Strategy, Massachusetts Food System Collaborative, and Rhode Island Food Policy Council.

wholesale customers by Farm Fresh’s Market Mobile

food service.

(Farm Fresh Rhode Island)

By the end of our spendout, all New England states had active food system planning initiatives underway, and three of them—Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont—had direct state government support and involvement. With JMF’s help, food system planners in all six states had also developed a community of practice (COP) to share ideas and resources on a regular basis and, more generally, to help build collective momentum.

In 2019, this community of practice became a formal nonprofit entity called the New England Food System Planners Partnership. The partnership, in turn, joined with Food Solutions New England to launch a 10-year planning initiative co-funded by JMF called New England Feeding New England (NEFNE), which had the overarching goal of improving the reliability of the regional food system.

Specifically, NEFNE called for strengthening supply chains and preparing the food system for shocks from climate-related weather events—a mission that, with the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020, was expanded to address shocks from public health emergencies. The initiative set a goal for New England to harvest or produce 30% of its food by 2030.

Timely support to help states turn plans into practice was critical, said Kenneth Ayars, chief of the Rhode Island state Division of Agriculture, in 2022. He cited a two-year, $250,000 grant made by a private donor, the Henry P. Kendall Foundation (HPFK), and JMF’s funding that helped Rhode Island pay the first two years of salary for the state’s first-ever director of food strategy.

“With all that happened in the pandemic and with climate change bearing down on us, having a [food system] strategy and a point person entirely focused on implementing that strategy has been critical,” Ayars said in 2022. “Our division spans everything from control of mosquitoes and invasive insects to forestry, but the food system is now almost the core of our efforts. It has proven so valuable. We saw during the pandemic that if we hadn’t begun this effort when we were not in crisis mode, it would’ve been that much more of a challenge.”

Access to policymakers

Several years into the spendout, we recognized a need to help New England advocates advance their regional food system goals at the federal policy level as well. Competing to be heard in Washington, D.C., above the voices of “Big Ag” interests from the Midwest and West would not be easy, but we eventually found an ideal grantee partner in the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC). NSAC used its expert staff and long experience to help our region make its case to federal legislative and executive bodies.

We also helped fund the Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Working Group (NESAWG) to ensure that the interests of the region’s urban growers, producers of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, food justice advocates, and youth were represented in the federal policy arena.

An important opening for regional advocates appeared in 2014, when Chuck Ross, then Vermont’s secretary of agriculture, invited us to sponsor a delegation of sustainable farming advocates at the annual conference of the National Association of State Departments of Agriculture (NASDA).

of the Northeast Association of State

Departments of Agriculture

(Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Working Group)

Ross chaired NASDA that year, which meant the conference would occur on his home turf. JMF, the Kendall Foundation, and other philanthropic partners pulled together funding to allow Food Solutions New England (FSNE) to become the conference’s top sponsor, a role previously played by agribusiness giants such as Monsanto, Conagra, and John Deere. As a result, New England advocates for sustainable agriculture practices, smaller-scale producers, farm- and food-chain workers, and everyday consumers were spotlighted for the first time at this annual gathering of state-level food and agriculture decision-makers from across the country.

Sponsorships of this kind continued at the national conference, and starting in 2015, JMF and its funding partners underwrote the attendance of sustainable-food advocates at annual meetings of NASDA’s Northeast chapter. That practice, in turn, was extended to NASDA chapter meetings nationwide with support from the Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems Funders (SAFSF), a philanthropic affinity association.

Investment tools

Grants were not our program’s only means of advancing food system goals. Though grants made up the vast bulk of our program activity, we also made use of program-related investments (PRIs) and market-rate investments (MRIs).

The guidelines we created for PRIs required:

- That these investments align with the goals of one or another of JMF’s programs;

- That they be timed such that returns on investment would reach the foundation in time for those dollars to be redeployed as grants before the end of the spendout period; and

- That the program agree to debit its budget, all at once or in annual increments, in the amount of the investment until those dollars returned to the Fund.

In the end, the farm and food grantmaking was the only one of JMF’s four programs to take advantage of the PRI option during the spendout era. The first of two such PRIs was a 2006 co-investment opportunity with Vermont-based philanthropy partners Castanea Foundation and the High Meadows Fund to help a former cow dairy convert to a goat dairy.

That project’s immediate aim was to help Vermont Creamery, a maker of goat cheese, source more of its goat milk from home-state dairies. As of the end of our spendout, the Ayers Brook Goat Dairy was doing just that, producing antibiotic- and hormone-free goat’s milk for Vermont Creamery and Fat Toad Farm, maker of goat’s milk caramels.

(Ayers Brook)

Ayers Brook Goat Dairy also was fulfilling other key goals: to enhance U.S. goat dairying by improving the genetics of its Saanen herd, and to serve as a resource for other Vermont farmers interested in transitioning from conventional dairy to goat dairy operations or starting goat dairies from scratch. The $250,000 that JMF invested in Ayers Brook was returned to the foundation in 2017 for use in our farm and food grantmaking.

Our farm and food area’s other PRI was a loan of $425,000 in 2013 to the Northeast unit of the Fair Food Fund (FFF), a national impact investor that helps finance local projects with potential to expand the food economy.

To obtain a loan from FFF-Northeast, food businesses had to source at least some of their ingredients from farmers in the region to ensure a “knock-on” effect for growers and others in the regional food supply chain.

Fair Food Fund also provided technical assistance for entrepreneurs. Although Fair Food Fund was prepared to repay the full amount of JMF’s loan, plus interest, on time in 2021, we agreed to allow it to retain a portion of the loan so it could ease the debt burden of borrowers most severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Resilience writ large

The outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 wreaked havoc in many ways, not least by disrupting much of the world’s vertically integrated food system. For all of its logistical sophistication and economic might, that system proved itself surprisingly ill-equipped to cope with an external shock of the pandemic’s magnitude.

Yet in New England, as elsewhere in the country, local and regional food system participants adapted impressively in real time to keep neighbors fed and farmers supported.

For instance, as COVID-19 closed schools, community centers, and other places that served regular meals, grantee partners including Farm to Institution New England and the Massachusetts Food System Collaborative jointly served as an information clearinghouse to report on emerging needs.

Farm Fresh Rhode Island, Food Connects, Red Tomato, the Center for an Agricultural Economy, CommonWealth Kitchen, and the Western Mass Food Processing Center, among many others, also responded. They pivoted from their regular work to get foodstuffs and prepared meals to neighbors in lockdown and to maintain business for local farmers and food producers.

As the pandemic ground on and government assistance became available, JMF technical-assistance partners swung into action. Organizations including The Carrot Project, NOFA-Vermont, the New Hampshire Community Loan Fund, the Fair Food Fund, the Vermont Farm and Forest Viability Project, and Land for Good helped farmers and food enterprises apply for grants and obtain paycheck-protection assistance.

Eventually, many of these farmers, food hubs, and food entrepreneurs sought and won USDA contracts to supply boxes of vegetables, fruits, dairy, protein, and other basic foods to families and individuals in need.

For experts such as Ela Chapin, former head of the state of Vermont’s Farm and Forest Viability Program, the pandemic not only illustrated the progress made; it also underscored the importance of building aggressively on those gains in the future.

“We used to think there would be a slow transition to regional and local food systems due to consumer trends, climate change, and the approach of peak oil, but what we have learned is that this transition will not be so smooth,” Chapin said in 2022. “Have we met our goals, such as getting regional food into institutions as widely as we wanted? Not yet. But we’ve helped to lay important foundations by encouraging the creation of regional food businesses and market channels. We have done the research, built regional systems, and we know what to do.”

Added Chapin: “Because of the amazing work of producers and food systems organizations, our region was ready to pivot, solve supply chain problems and meet local and regional needs during the pandemic. It is essential to take advantage of this opportunity and continue to build regional and local food systems so that when environmental externalities are reflected [in price and supply chain pressures], the regional food system will fully support our communities.”

Racial equity

As ever throughout JMF’s spendout, the Henry P. Kendall Foundation was our most stalwart and generous funding partner during the pandemic. With its focus on food in institutions of higher education, Kendall had become a fraternal twin of sorts as we pursued our farm and food program—albeit the heftier of the two, with its annual budget several times that of JMF’s.

By April 2020, JMF and Andy Kendall, president of the Kendall Foundation, had co-created a plan to leverage contributions from our two foundations and other philanthropic partners to establish a $1 million pandemic-response fund.

(The Grassroots Fund)

The New England Food System Resilience Fund was originally designed to shore up the regional food system in a time of unprecedented disruption, and, with that goal in mind, made 11 “reinforcement” grants in 2020 totaling just under $350,000.

But George Floyd’s murder just one month after these initial grants went out the door and the ensuing national reckoning with racial injustice prompted JMF, the Kendall Foundation, and the other original donors to rethink the Resilience Fund’s purpose. We concluded that it should serve not only to respond to the ongoing pandemic, but also to address the racial inequities at work in the food system and in prevailing philanthropic practice.

So by fall 2020, the Resilience Fund’s remaining balance of $650,000 had moved to the New England Grassroots Environment Fund, an organization with expertise in participatory grantmaking. Contributions continued to be raised, eventually topping the original $1 million goal.

Though the support for the New England Grassroots Environment Fund represented our program’s first explicit attempt to address racial inequities, some of our grantees had been doing important work to alleviate socioeconomic unfairness in the food system for years. Migrant Justice’s Milk with Dignity program, for instance, sought to improve working conditions for the region’s migrant farmworkers.

the Milk with Dignity program.

(Migrant Justice)

After developing a set of fair labor standards and successfully pressing Vermont-based Ben & Jerry’s to require their adoption by its milk suppliers, the campaign in 2021 began pressing the Maine-headquartered Hannaford supermarket chain to do the same.

We helped other grantees—in many cases food banks—take aim at food insecurity, too. In 2009–2011, for instance, JMF and partner funders helped Maine’s Good Shepherd Food Bank buy from in-state farmers so its clients would receive fresh produce rather than the sometimes nutritionally dubious processed foods often dispensed by U.S. food pantries. The program expanded rapidly, with 80 Maine farms growing 2.2 million pounds of food for Good Shepherd in 2021.

Such was the success of Good Shepherd Food Bank that by fall 2022, the nonprofit food bank was preparing to launch a wholly owned for-profit public-benefit subsidiary called Harvesting Good. The new corporation plans to sell Maine-grown products to retailers and wholesalers throughout the Northeast and to use the proceeds to supply frozen produce to Good Shepherd and other members of Maine’s charitable food network.

(Good Shepherd Food Bank)

For some grantees, equity work evolved to become the core of their mission. When Food Solutions New England (FSNE) was established in 2010, for instance, it was a network of overwhelmingly white experts and advocates promoting small-scale, sustainable agriculture. By 2020 it had become a multi-racial collaboration committed not only in its words, but also through its actions, to the idea that a healthy New England food system cannot be achieved without equity, dignity, and well-being for all.

Full circle

It was perhaps fitting that near the end of our spendout period, funds from JMF found their way, albeit indirectly, back to the Mettowee Valley.

(Merck Forest and Farmland Center)

The funds had been conveyed to three family foundations that were set up in 2010 by Buechner family members who had left the JMF board. The three foundations jointly completed several pending farmland conservation projects in the valley. They also underwrote a project allowing Merck Forest and Farmland Center to obtain 144 acres adjacent to the Mettowee Valley’s main elementary school to create outdoor learning and recreational space for the students, 50% of whom are economically disadvantaged.

“JMF and the Merck family have put a lot into conservation in the Mettowee Valley, and this was giving back, wrapping around the school like a hug,” said Donald Campbell of the Vermont Land Trust, which holds a conservation easement on the land. “It has almost nothing to do with agriculture, but everything to do with connecting people to the land, to the outdoors, and to the future.”