Health and Environment Grantmaking

Table of Contents

There is arguably no field in which The John Merck Fund and its advocacy partners made a greater, more fundamental mark than environmental health.

When our health and environment grantmaking began in 1996, growing organically out of the funding for clean energy that we had carried out since 1987, U.S. environmental health advocacy lacked capacity and coordination. For the most part, the field consisted of small nonprofits that, while passionately dedicated, were underresourced and often acted alone to address individual chemicals of high concern.

But successful experimentation and progress in clean energy advocacy demonstrated that powerful synergies existed between the issues of environmental health and climate protection. These connections were especially evident in the case of air pollution from sources such as coal-fired power plants and diesel-fueled vehicles.

Trustees resolved to help key advocates spotlight such connections through a new program that would seek to curb harmful chemical exposures while working more broadly to strengthen the field of environmental health.

The health and environment program that emerged had four main strategic goals, the first of which was to improve existing advocacy addressing pollution from mercury, dioxins, and diesel emissions—all of them byproducts of burning fossil fuels.

Our second aim reflected the view of key grantee partners that the 1990s-era strategy of tackling one bad-actor chemical at a time had proven far too slow. We resolved to help advocates “go big” by targeting a broad class of harmful compounds—persistent, bioaccumulative toxic chemicals (PBTs)—and promoting the precautionary framework that guides chemical regulation in Europe.

The new program’s other two strategic goals were to create strong market signals favoring chemical safety—both through regulatory policy initiatives and consumer campaigns—and to assist environmental health advocates in improving and coordinating their public communications.

In the ensuing 25 years of work, we encountered some undeniable disappointments, perhaps the biggest being the failure of efforts to implement meaningful chemicals policy reform at the federal level in the face of intense industry and Republican-allied opposition.

And while the issue of chemicals in the environment gained significant visibility during this period, it did not manage to attract the extensive national-scale exposure and advocacy funding needed to overcome the political pushback. Too often, it was overshadowed by higher-profile climate policy battles and emergencies ranging from the Great Recession of 2007–2009 to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite these disappointments, our grantees helped engineer extraordinary advances. These included important policy innovations in individual states, transformational consumer demand for toxin-free products, and public awareness of the pernicious developmental toll that environmental toxins take on children throughout the country and the world.

Our grantees also co-created a broad environmental health-advocacy ecosystem comprising partnerships among legal and policy experts, scientists, corporate allies, market and grassroots campaigners, community groups, and communications specialists. Collectively, these stakeholders have become a formidable force whose presence significantly boosts the likelihood of future progress in chemicals policy.

and president of Health

Care Without Harm

“Twenty-five years ago the movement for environmental health and justice was defending communities against toxic dumps and incinerators,” Gary Cohen, founder and president of longtime JMF grantee Health Care Without Harm, said in 2022. “With consistent funding from The John Merck Fund and support from additional funders along the way, that same movement has now dramatically matured and expanded, and is fundamentally challenging an economy that is built on fossil fuels, toxic chemicals, and industrial agriculture.”

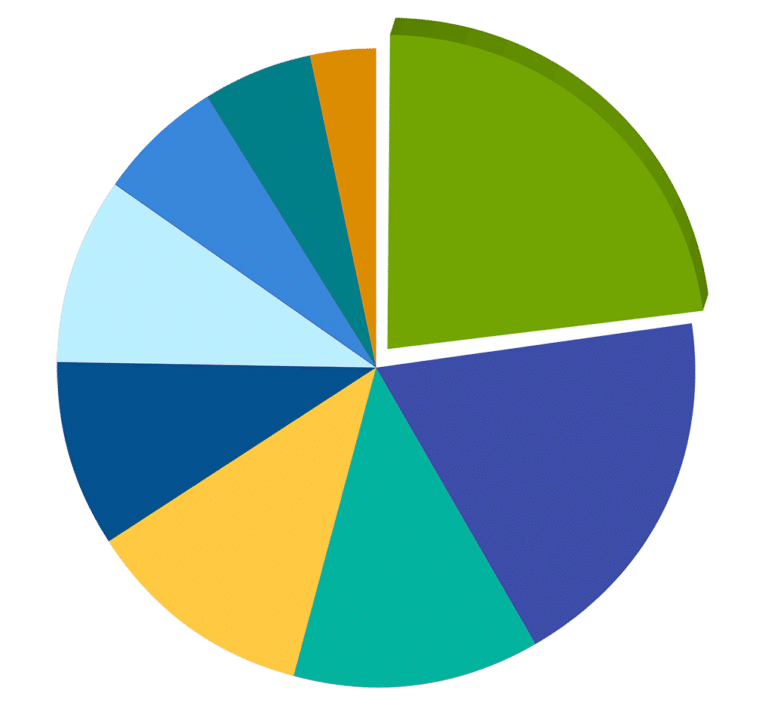

JMF Grants 1996-2021: Health and Environment

Total $ Amount

$68,577,809

Years of Program

1996-2021

# of Grants

1,146

New paradigm

When JMF launched its health and environment grantmaking in 1996, what was then called “toxics” advocacy was dominated by a few small but scrappy groups that concentrated on certain individual pollutants. These groups usually operated at the periphery of larger, more multidimensional environmental organizations and often lacked coordination.

An early goal of our program was to help these advocates develop new, more relatable ways to urge curbs on three types of pollution in particular: mercury, dioxins, and diesel emissions.

A key strategy in that regard grew out of successful work by our clean energy grantees to emphasize public health concerns in their campaign to close or clean up New England’s 16 coal-fired power plants. Highlighting the connection between climate change and human health, these advocates helped the public understand how emissions from coal plants not only spewed heat-trapping carbon dioxide, but also harmful chemicals including mercury, which can seriously affect brain development and health.

Similarly, health and environment advocacy partners showed how diesel-powered vehicles such as buses and trucks, in addition to sending carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, emit particulates and toxic chemicals that cause respiratory illness and developmental delays—often disproportionately in low-income communities.

Our grantee partners also helped ensure that the sources of these pollutants were addressed more comprehensively. For instance, Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR) and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) led a coalition that fought for strong federal limits on mercury pollution.

Beyond power plants

At the same time, the grassroots advocacy organization Clean Water Fund spearheaded the multi-state New England Zero Mercury Project, a comprehensive effort to curb all major mercury pollution sources beyond power plants, including waste incinerators, medical equipment, and consumer batteries.

And a lawsuit launched with JMF funding in 2000 by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and Maine People’s Alliance (MPA) targeted mercury pollution in Maine’s Penobscot River.

The litigation centered on HoltraChem chemical company’s dumping of up to 13 tons of mercury into the river near its Orrington, Maine, plant beginning in 1967. In 2002, HoltraChem’s successor company, Mallinckrodt US LLC, was found liable in Maine federal district court. After years of court-ordered scientific study confirmed mercury pollution in Penobscot River estuary sediment and wildlife, a federal judge in 2021 approved a settlement requiring Mallinckrodt to pay $187 million in cleanup costs and $80 million in contingency funds.

Additional JMF funding went to the Mercury Policy Project, which used deep expertise and multiple partnerships to press successfully for international controls on multiple mercury-pollution sources.

When JMF stopped focusing on mercury pollution in 2010, virtually all U.S. sources of mercury exposure had been reduced, controlled, or eliminated, thanks to New England advocates and their counterparts in other regions and nationwide.

At the same time, grantee partners Health Care Without Harm, the Center for Health, Environment & Justice, and Toxics Action Center (later renamed Community Action Works) conducted a regional effort to rein in dioxin pollution, which is produced in the manufacture or burning of fossil fuel-based plastics. Though their campaign was not as comprehensive, it resulted in the closure or retrofitting of most medical and municipal waste incinerators in New England.

In the transportation sector, grantee Alternatives for Community and Environment led a campaign that successfully pressed Boston to convert its municipal bus fleet from diesel fuel to natural gas, a transition that reduced the city’s carbon footprint while improving air quality in local neighborhoods. Another of our partners, the Clean Air Task Force, went beyond the local level to mount strategic state campaigns in New England, the Midwest, and the Southeast to eliminate toxic and climate-damaging diesel emissions from school buses.

Simultaneously informing this work was the growing scientific understanding of links between fossil fuel-generated air pollution and health impacts, particularly in children. Among the key contributors to this understanding were JMF grantees such as the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health and its community partner WE ACT for Environmental Justice.

JMF sought not only to promote the public dissemination of this work, but also to support grantees as they integrated it into their programming. A prime example of the latter was the work of longtime grantee Health Care Without Harm. Under the leadership of Gary Cohen, Health Care Without Harm led the fight to shut down medical-waste incinerators and to eliminate mercury in medical equipment such as thermometers and blood pressure devices. It also helped persuade the healthcare sector to address its climate impacts in keeping with its mandate to “first do no harm.”

Consumer focus

Though the new emphasis on health was instrumental in spotlighting the threats posed by mercury, dioxin, and diesel-emission pollution, it proved especially potent when advocates expanded their focus to include chemicals found in consumer products.

Advocates could point to research showing that many chemicals found in goods ranging from cosmetics to pesticides and in packaging such as plastic water bottles and yogurt cups can compromise the endocrine system by interfering with the body’s hormones. The human health impacts of these chemicals, known as endocrine disrupters, have been linked to developmental, reproductive, brain, and immunological problems, according to the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

(ricardo/zone41.net)

To draw attention to endocrine disrupters, advocates teamed up with experts such as biologist and Environmental Health News publisher Pete Myers, a JMF grantee whose work has played a major part in deepening scientific and public understanding of these chemicals.

To help make the potential risks of chemical exposure relatable to the public, advocates organized “body burden” testing in which volunteers’ blood, urine, breast milk, and umbilical cord samples were analyzed for toxic chemicals.

Thought leaders working with support from other foundations and institutions provided crucial perspective as well. Among them was Philip Landrigan, a pediatrician and epidemiologist at New York University and later Boston College, whose research helped show how toxic chemicals can compromise children’s brain development and immune systems.

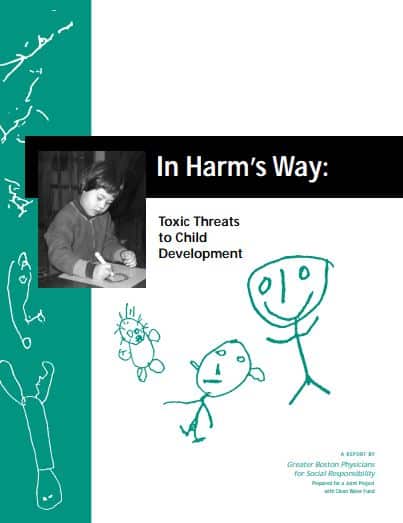

A major contribution to the understanding of chemical impacts on children’s health and development came in 2000, when the Boston affiliate of Physicians for Social Responsibility published In Harm’s Way: Toxic Threats to Child Development. This peer-reviewed report, whose preparation was led by physician Ted Schettler, synthesized what was known and what was conjectured about potential links between toxic chemicals in the environment and children’s learning, behavioral, and developmental disabilities.

Featuring a version for the general public as well as fact sheets and training materials for health professionals, the report concluded that neurodevelopmental disabilities “are widespread, and chemical exposures are important and preventable contributors to these conditions.” It also challenged policymakers by citing repeated regulatory failures “to protect children from exposures to developmental neurotoxins,” asserting that these failures “can often be traced to the influence of vested interests upon the regulatory process.”

Two subsequent Physicians for Social Responsibility compilations, both co-funded by JMF, addressed the impacts of chemical exposures on reproductive health and geriatric health.

Overall, the new public health emphasis and the science behind it moved attention from polluted ecosystems to concerns much closer to home, allowing organizations to build support for their work by connecting with more people in their everyday lives. The iconic bald eagle threatened by DDT pesticide was beginning to be replaced in the public’s mind by a child with developmental delays caused by endocrine-disrupting chemicals in toys, food, and clothing.

(Toxic-Free Future)

The public health framing also allowed the movement to draw in advocacy groups that previously had not focused on environmental toxins but now came to recognize the role of chemical exposures in the core health problems they were addressing.

Figuring prominently in the creation of this network was the Collaborative for Health and Environment, an initiative of Commonweal, a California-based health and environment research and network-building institute. Launched in 2002 under the leadership of Michael Lerner, Commonweal president and founder, the collaborative established environmental health working groups active in more than a dozen disease fields ranging from breast cancer and diabetes to autism and neurodegenerative diseases.

In addition to providing some of the collaborative’s general support, JMF helped intellectual- and developmental-disabilities advocates bring the emerging science on endocrine disrupters to bear. Grantees including Columbia University’s Center for Children’s Environmental Health, Commonweal’s Learning and Developmental Disabilities Initiative, and Project TENDR, a multi-disciplinary network of experts, used the new knowledge to underscore the dangers that chemical exposures pose to infants and children.

JMF also assisted advocacy groups such as the Learning Disabilities Association of America, The Arc, and the Autism Society as they drew on this evidence to make environmental health a primary part of their mission.

‘Going big’

With some 80,000 chemicals in the marketplace and only a few hundred of them regulated, advocates and scientists recognized that the environmental health field was not moving fast enough. Inspired by advancements in Europe, advocates in the early 2000s launched a far more comprehensive attempt to reduce use of all chemicals defined as “persistent, bioaccumulative toxins,” or PBTs. They pressed as well for a preventative approach, also borrowed from Europe, known as the “precautionary principle,” which held that chemicals must be proven safe before their commercial use could be allowed.

If such a policy were possible in Europe, JMF and its grantee partners perhaps naively reasoned, then comprehensive chemicals policy could be adopted in the United States as well. We knew, though, that such a goal would be unobtainable at the federal level given opposition not only from certain industry groups, but also their political allies in Washington.

So we set out to establish policy precedents at the state level first, building multi-constituency advocacy coalitions in five states—Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, and Washington. All but one of these coalitions, the one in Massachusetts, helped engineer successful enactment of state chemicals policies. The policies varied from state to state, but in several cases they banned entire classes of chemicals such as flame retardants, and some prohibited certain chemical applications, for instance those involving children’s products. And all of them attempted to establish coherent, science-based systems for flagging chemicals of concern.

By 2007 the state coalitions had built a network with centralized coordination known as SAFER, which JMF also supported. And as we completed our spendout in 2022, SAFER was overseeing activities in 38 states and had played a critical role in Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families, a coalition of 450 advocacy groups and business allies. In 2016, Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families succeeded in pushing Congress to finally enact legislation overhauling federal chemicals policy.

(Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families)

Critically needed reform of the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) was enacted in 2016 thanks largely to negotiations led by Andy Igrejas, founder of Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families. In some respects, the bill that emerged was seen by advocates as weaker than hoped; but overall it was regarded as an enormously encouraging first step in regulating toxic chemicals nationwide.

However, the Environmental Protection Agency under then-President Donald Trump effectively weakened the regulations written to enact the law and then did virtually nothing to enforce the legislation. At the close of JMF’s spendout, the administration of President Joseph Biden was moving to address a few of these problems, fueling hope that the law eventually might function as intended.

Uneven federal progress did not obscure strides being made in individual states, where advocates built consumer demand for safe products and parlayed that support into policy wins that made children’s products, electronics, and furniture safer, and that also removed hazardous chemicals from food packaging. Policy reforms in leading states were then replicated in other states, prompting corporations to take notice. That dynamic helped propel the virtual elimination of toxic flame retardants from household furniture, children’s products, and eventually even firefighting foam.

(Toxic-Free Future)

Using all of the expertise and resources built over the decade, 11 states in 2018 began capitalizing on the momentum by banning an entire class—PFAS. This action, in turn, later prompted federal action on firefighting foam used by the military and in airports. Our grantee partners loomed large in these successes, most of which were bipartisan.

Harnessing markets

A critical learning for the environmental health field was that market mechanisms can often advance an agenda faster than conventional policy development. Accordingly, JMF leveraged the interplay between public policy, corporate decision-making, and consumer behavior throughout its grantmaking.

Understanding that the European Union was important from a markets perspective in addition to its potential to set policy precedents, JMF supported ChemSec (the International Chemical Secretariat) and World Wildlife Fund as Europe developed a far-ranging comprehensive chemicals policy known as REACH. As anticipated, American corporations doing business in Europe were pressured to produce safer, healthier products for a consumer market larger than the United States.

(Defend Our Health)

At the same time, companies were being forced to respond to environmental health campaigns underway in several U.S. states. The campaigns included many that JMF supported at organizations such as the Center for Environmental Health, Coming Clean, the Ecology Center, the Environmental Health Strategy Center (now Defend Our Health), and Toxic-Free Future. The campaigns prompted improvements in corporate chemicals policy by encouraging consumers to factor environmental health into their purchasing decisions.

The Ecology Center provided influential sampling and analysis of chemicals in baby-centric consumer products such as car seats and strollers, eventually creating a website (https://www.ecocenter.org/our-work/healthy-stuff-lab), that was reporting on hundreds of products by the end of JMF’s spendout.

SAFER’s superb coordination of consumer campaigns in multiple states loomed large in successful prohibitions on toxic flame retardants. Meanwhile, Toxic-Free Future’s Mind the Store campaign attracted the begrudging attention of major retailers by publishing regular public report cards on corporate performance in adopting hazard-based, precautionary chemical policies and reducing the use of toxic chemicals in their products.

In addition to publishing its report card, Mind the Store released product-testing information, conducted shareholder advocacy, and maintained behind-the-scenes engagement with retail decision-makers. These activities led major retailers like Walmart, Target, CVS Health, and others to develop and implement comprehensive safer-chemicals policies. For its part, Coming Clean organized comparable campaigns to bring improvement to product lines in the Dollar Store, Dollar General, and other chains with largely low-income clienteles.

JMF also supported an “inside” strategy of engagement with key companies and product categories through grants to initiatives such as Clean Production Action’s GreenScreen for Safer Chemicals and Chemical Footprint Project, and ChemSec’s SIN List; Healthy Building Network’s Pharos database, which catalogs the chemical contents of building materials; and the Lowell Center for Sustainable Production’s Green Chemistry & Commerce Council.

(Clean Production Action)

These projects all created specialized tools that are now being used by many companies to assess the safety of chemicals in their products, identify superior alternatives, and provide safer products for their customers. These activities illustrate how close, long-term engagement between a funder and advocacy partners can have far-reaching and lasting effect.

“Three things that have been critical about The John Merck Fund’s approach have been trust, creativity, and long-term investment,” Laurie Valeriano, executive director of Toxic-Free Future, remarked for this report in 2023. “They trusted our strategies, and we were able to build long-term relationships with environmental health groups, health professionals, firefighters, and health-impacted organizations to win major reforms to governmental and corporate chemicals policies from Washington state to Washington, D.C., to Walmart.”

(Toxic-Free Future)

Added Valeriano: “[JMF’s] early strategic insights supporting a demand-side strategy allowed us to show that markets could make major shifts in the systems to safer solutions that were not only possible but cost-effective, which was instrumental in many wins. And [JMF] funded groups for the long term, allowing groups like ours to really establish ourselves, build expertise [and] relationships, and eventually join with Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families and Mind the Store to build an even more effective, sustainable organization.”

(Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families)

Power of communication

As important as communications are to social-change advocacy, environmental groups have often found it hard to connect meaningfully with people beyond their core supporters. We and our grantee partners recognized that training, experimentation, and, often, dedicated resources were needed to build new, more diverse health and environment constituencies.

With that in mind, JMF backed experiments in outreach to developmental and learning disabilities groups, seniors, people of faith, and mothers of young children. We helped organizations with constituencies outside conventional environmental circles to develop environmental health information and calls to action in language that resonated with their members.

A complementary set of grants enabled certain advocacy groups to serve as hubs, modeling communications strategies and replicating them for use by their peers. Offering communications training, message development and dissemination, and opinion research, these groups included Clean Production Action; Coming Clean; Defend Our Health (formerly Environmental Health Strategy Center); SAFER; Safer Chemicals Healthy, Families; and Toxic-Free Future.

The most ambitious communications and movement-building effort was that of Healthy Babies Bright Futures (HBBF), which created a campaign to curb the use of chemicals that can alter the brain development of babies in their first 1,000 days of life, possibly leading to lifelong deficits and disabilities. Launched with a JMF leadership grant in 2014, the initiative was preceded by an analysis aimed at determining how large donors could be induced to underwrite the ongoing advocacy needed to engage parents, families, and other essential stakeholders nationwide.

The campaign’s coalition of advocates, scientists, and funders worked to galvanize environmental health activism around the emerging consensus that heavy metals, air pollutants, pesticides, and certain endocrine disrupters pose particularly grave threats in the crucial early stages of brain development. Engaging with parents, municipal governments, and corporate partners, coalition members highlighted the specific health risks these exposures pose to babies and toddlers, and identified simple, effective ways to avoid them.

In the process, HBBF successfully influenced government policies and corporate practices. For instance, it co-led a successful drive to remove heavy metals from baby foods, coordinating with advocacy partners across the country to test baby formulas, infant rice cereal, and commercial and homemade baby foods for these toxins. With contaminants detected in more than 90% of the baby foods tested, HBBF helped disseminate information on the risks to parents and other advocates for children’s health, and worked successfully with food companies to begin addressing the problem.

HBBF’s Bright Cities program, meanwhile, prompted authorities in 35 U.S. cities to implement practices designed to protect infants from exposure to toxic chemicals. And another HBBF program assisted in reducing lead concentrations in the drinking water of 1,000 families.

Despite this progress and the potential for more, HBBF did not manage to bring substantial new funding into the environmental health field, a challenge that remains for advocates and future funders. Although JMF reached the end of its spendout in 2021 and its anchor funding for HBBF expired, the initiative continued to innovate with support from other sources, advancing high-impact interventions that reduced babies’ exposures to harmful chemicals.

Bright Futures

Charlotte Brody, a prominent environmental health strategist who leads HBBF, summed up the impact of HBBF this way in 2022: “The 3.7 million children that will be born this year in the United States have less arsenic and lead in their food and water, and really do have a better chance to be healthy babies with bright futures.”

New advocacy tools

By the end of our spendout, we were mindful that citizens, advocates for vulnerable populations, consumer groups, companies, and the broader environmental movement all had a long way to go to rid the world of harmful chemical exposures. But they now had an unprecedented array of tools at their disposal.

A quarter century of collaborative advocacy had enabled a remarkable evolution and maturation of the field. The small, passionate nonprofits we encountered at the outset had developed into a thriving network of advocates with the complementary skills and integrated capabilities needed to drive systemic social change. And efforts by JMF—in particular by our longtime executive director, Ruth Hennig—to help advocates look beyond their individual projects and plans had found fertile ground, boosting prospects for advances in the years to come.

“JMF didn’t just fund environmental health,” HBBF’s Charlotte Brody said. “The foundation pushed all of us who were focused on the health hazards of chemicals to move beyond the grandiose language of our grant proposals into more sensitive, savvy, and strongly strategic ways of working.”